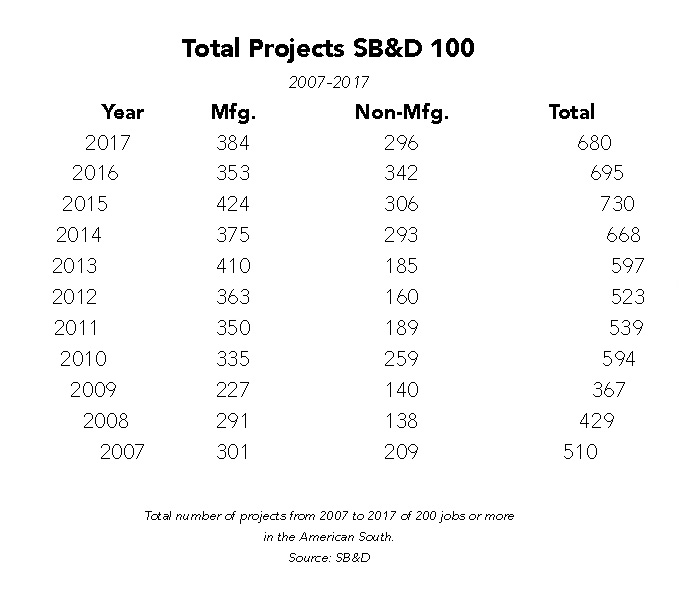

The South’s economy, the third largest economy in the world, has been humming along quite nicely since 2010 when 594 projects were announced meeting or exceeding SB&D 100 thresholds. The SB&D 100 is a ranking published each spring quarter identifying and totaling all economic development projects announced in the 15-state American South during the previous calendar year that meet or exceed 200 jobs and/or $30 million in investment.

Congratulations are certainly in order. Large project activity in the South in the fall 2018 quarter was the best in history. We saw a 25,000-job project (Amazon in Northern Virginia), two 5,000-job projects (Apple in Austin and Amazon in Nashville) and every one of the top 10 deals announced in the fall quarter were 1,000 jobs or more, a feat only accomplished in about 15 quarters in the last 25 years. (You can see the top 10 deals for the fall 2018 quarter announced in the South on page 72 of this issue.)

Yet, while we celebrate the best quarter of deals in the South’s history, we have to factor in that summer and fall 2018 quarters were two of the worst deal-making quarters in the last 25 years in the South’s automotive sector, one key indicator on how the economy is faring. The South is home to 15 foreign-owned assembly plants with another (Mazda Toyota) being built in Huntsville, Ala. Foreign-owned assembly plants and well over 1,000 foreign-owned parts suppliers represent a huge chunk of the South’s economy.

One indicator that is being overlooked regarding the economy is the fact that foreign direct investment in the U.S. dropped to $259 billion in 2017 according to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. That is a 41 percent drop from the historic high of $439 billion in calendar year 2015. In a typical year, the 15-state American South captures about half of all FDI in the U.S. Foreign deal activity has slowed dramatically since 2015.

Why measure an economy by economic development project activity? Project activity, we believe, is the best way to assess an economy, accelerated or lethargic. In struggling economies, project activity slows. In a fast moving economy, project activity picks up, especially on the front end of an economic expansion. Then, as the expansion matures, it hits a sweet spot, the peak of the cycle. We believe the sweet spot of this expansion occurred in 2014 and 2015 and we have the data that supports that claim.

At the same time, there are some economic development indicators that show that this economic expansion may not have peaked yet, but they are fewer in number compared to those indicators that show that this economic cycle peaked three or four years ago.

President Trump’s first year in office (2017) saw 680 projects meet or exceed our thresholds in the annual SB&D 100. Historically, it was an exceptional year, yet 2017 was down from the all-time high of 730 big deals in 2015 and 695 in 2016.

Job generation has also slowed from its peak in 2014 with an average of 250,000 jobs created in the U.S. per month that year. In fact, it started to slow down in 2015 when the average monthly job gains in the U.S. dropped slightly to 226,000. The average monthly job gains in 2017 were 182,000, but they have risen so far this year with an average of 193,000 jobs per month created, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The key factor in job generation slowing the past couple of years is that we are at full employment, and there are no doubts about that. The U.S. is sporting the lowest unemployment rate since the late 1960s. Throw in a baby bust, and there are just not many folks left to hire. The country’s population hasn’t grown by over 1 percent in 16 years. . .a time when the Baby Boomer generation — the largest generation in U.S. history — is aging out of the workforce by millions each year.

In other words, the lowest fertility rate in the history of the country occurring now means workers aging out cannot be replaced in coming years. For decades after World War II, the U.S. could count on an average of 200,000 people turning working age (16) each month. This 16-year baby bust has brought that figure down to an average of 70,000 people turning working age each month the last three years. The biggest challenge this country is facing now, and for many years to come, is that too few people are being born and too many people are aging out of the workforce.

There are currently about 7 million unfilled jobs in the U.S., with no more than 1.6 million people taking those available jobs each year. So, job generation is going to slow in coming years because we are at full employment and a variety of other reasons, such as cutting visas and legal immigration, a lack of comprehensive immigration laws, and the lowest birthrate in the nation’s history.

Some economists believe we are currently beyond full employment. What is keeping the job-generating mill running are the 3 million people per month who are job-hopping. Since April, the U.S. has averaged 3 million people quitting their jobs for better jobs per month. And we have also averaged over 1.5 million layoffs per month during the last six months. If a slowdown is looming, which many economists believe, then there will be fewer workers job-hopping and obviously more layoffs.

Don’t get me wrong, we are not complaining about the current economy. We are still in the second longest economic expansion in this nation’s history, and the longest consecutive monthly job gain period ever. Yet, we are seeing the economy — based on total projects meeting or exceeding 200 jobs or more in the South — gradually slow. Not only that, as shown by the chart, monthly job gains have slowed in the U.S. since they peaked in 2014. The totals are certainly not alarming. However, in both sectors —

Don’t get me wrong, we are not complaining about the current economy. We are still in the second longest economic expansion in this nation’s history, and the longest consecutive monthly job gain period ever. Yet, we are seeing the economy — based on total projects meeting or exceeding 200 jobs or more in the South — gradually slow. Not only that, as shown by the chart, monthly job gains have slowed in the U.S. since they peaked in 2014. The totals are certainly not alarming. However, in both sectors —

project activity and job creation — it looks like the outstanding years of 2014 and 2015 have come and gone. Have the South’s and the U.S. economies peaked in this cycle?

That begs another question about the nation’s economy. Have the stock markets peaked in this economic cycle? They sure have been volatile, and overall the markets had their worst year in 2017 since 2008. In a quote from The New York Times in a story titled “The Stock Market’s Dangers Are Easier to See Now,” published November 30, 2018, economist James W. Paulsen, chief investment strategist of the Leuthold Group, said, “It gets somewhat easy, with a little experience, to recognize when you’re in the ballpark of a recession. That is where we are now, and that alone is quite a bit of information.”

Some indicators that show the economy is slowing

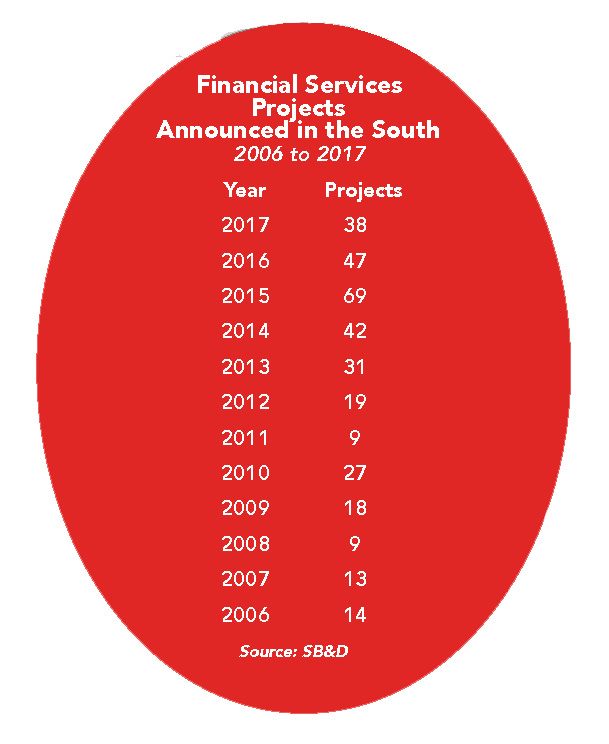

Southern Business & Development has learned over the years that one business sector in particular is a good indicator of whether the economy is growing or slowing based on its annual project totals announced each year in the 15-state American South. That sector is financial services.

Over the last 25 years, whenever the business climate is favorable, financial services thrive with lots of action in announced projects, particularly in the early portion of an expansion. We saw that in 2014 and 2015 when the financial technology (fintech) industry went nutty-nut in the South with tens of thousands of jobs announced, particularly in Atlanta, Dallas-Fort Worth and Charlotte. That fintech breakout has slowed to a trickle today.

Yet, even when the economy is perceived to be favorable (like now), financial services can fool you with a drop in projects. That is the inflection point when we believe — and financial services officials do, too — that the economy is curving in a different direction.

Financial services deals blossomed in calendar year 2015 with 69 projects of 200 jobs or more in the South. That was the all-time record since 1992 when SB&D began counting projects announced in the South. Financial services have averaged 42 large projects each year over the past 25 years. In the recession year of 2009 and even in the recovery year of 2011, there were only nine financial services deals meeting or exceeding our thresholds in the South, and only 19 in 2012 as the nation’s economy continued to recover.

The financial services industry, once slammed, takes several years to recover. So it’s clear to us that a rise or fall in financial services projects in the South go hand-in-hand with a rising or falling economy. You can easily determine that by looking at financial services deals in the years prior to the recession of 2008 in the chart. When we saw financial services projects drop from 41 in 2005 to 14 in 2006, we knew something was up. It was called a housing crisis, and the financial services industry was up to its neck in bad loans. Note in the chart, from 2015 to 2017, financial services deals in the South have dropped by 31 big deals.

The financial services industry, once slammed, takes several years to recover. So it’s clear to us that a rise or fall in financial services projects in the South go hand-in-hand with a rising or falling economy. You can easily determine that by looking at financial services deals in the years prior to the recession of 2008 in the chart. When we saw financial services projects drop from 41 in 2005 to 14 in 2006, we knew something was up. It was called a housing crisis, and the financial services industry was up to its neck in bad loans. Note in the chart, from 2015 to 2017, financial services deals in the South have dropped by 31 big deals.

Since the record total of 69 deals in the South in 2015, we have seen 47 big financial services deals in 2016 and only 38 last year. In studying the chart, while financial services deals are close to half of what they were in 2015, they are well above what occurred prior to and during the recession. Yet, the drop in deals in financials in the South is concerning.

So far this year, there is no question financial services deals are going to be down again. You can always tell how the economy is going and where it is going by following financial services deal activity. As they decrease year by year, the economy’s fitness, or lack thereof, can easily be measured.

In addition to financial services, the automotive industry is a prime indicator of the economy

In addition to financial services, the automotive industry is a prime indicator of the economy

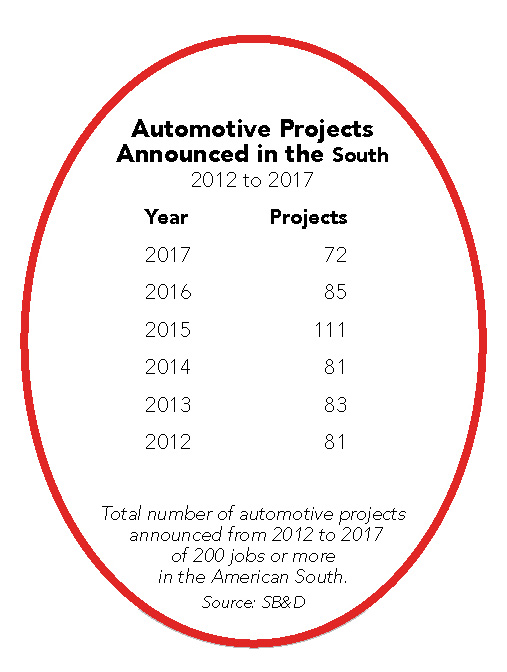

When lots of money is “on the street,” financial services deals rise. When lots of money is on the street, the automotive industry follows financial services with project totals that set records. In 2015, when we believe this economic recovery peaked, there were 111 automotive projects announced meeting or exceeding our thresholds. The 111 automotive projects in 2015 are an all-time high in the South. But that total dropped to 72 last year in the Southern Automotive Corridor (go to SouthernAutoCorridor.com), the worst total since 2009. Last year was only the second time in 25 years that the automotive industry wasn’t the No. 1 sector in large projects in the South. So when project activity in automotive starts to slow, it’s a sure sign the overall economy is slowing as well.

The automotive industry’s vehicle sales in the U.S. are an important indicator of consumer spending and consumer confidence. While vehicle sales are down slightly from the first of the year, much of 2017 sales dropped a fair amount, but recovered at the end of the year. Once again, vehicle sales peaked post-recession in — you guessed it — 2015.

Sure, Mazda and Toyota are building their new joint plant in Huntsville, Ala., but remember, Toyota was building its plant near Tupelo, Miss., right before the recession in 2008. The Japanese automaker delayed the opening of that plant until late in 2011 as a result.

And while we do have a new assembly plant being built in the Southern Auto Corridor — the first since Volvo and Mercedes-Benz Vans announced new facilities in South Carolina in 2015 — there are fewer assembly plants being expanded in 2018. We saw 18 automotive assembly plants in the South expand in 2014 and 2015. So, did the automotive industry — the South’s largest industry, by far — peak in 2015 as well?

The fact that in the fall quarter, GM announced it would close five plants in the U.S. and Canada and slash 15 percent of its salaried workforce is certainly a sign that the automotive industry is slowing as a whole. No automaker closes five plants simultaneously unless it is expecting slower sales in the near future. In 2015, when we believe this economic cycle peaked, there wasn’t a single automotive industry plant closure. In fact, most assembly plants in the South ran three shifts in 2015. That is no longer the case.

Housing and the building materials industry

Housing and the building materials industry

“The U.S. housing market is running out of steam, but its slowdown looks nothing like the historic collapse that took down the whole economy in 2007,” wrote Daniel Acker in a story published in October by The Wall Street Journal and Bloomberg titled, “Housing Market Positioned for a Gentler Slowdown Than in 2007.” If true, this is certainly good news, considering the housing market was so strong in 2014 and 2015. “Less strong” is much more palatable than the housing sector taking down an entire economy like it did in 2005 in some states, and in 2007 and 2008 in all states.

But you cannot ignore the fact that home sales have slowed this year as mortgage rates rise. Mortgage rates a full point higher than rates from last year are undoubtedly slowing purchases. In addition, the sweeping new tax law passed last December reduced home ownership tax deductions. The difference in the housing crisis of 2007 and the slowing of the real estate markets today centers on the fact that housing starts have not fully recovered from the last recession.

In my opinion, you can get a better picture of the housing market by looking at project activity in the building materials sector, which is slowing in performance in the South. In 2014, there were 35 large building materials projects meeting or exceeding our thresholds for a listing on the SB&D 100 that year. In 2017, that dropped to 13. So, the housing industry is slowing based on project activity from the building materials industry. And clearly, it peaked in 2014.

Petrochemicals is another sector that has slowed

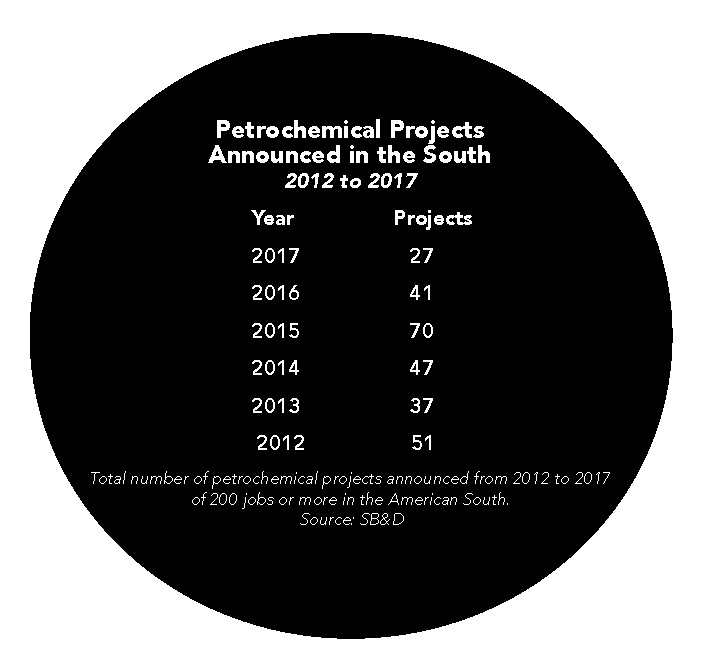

There are no bigger-ticket projects in the South than petrochemical or LNG projects. Most are multi-billion dollar deals, and an LNG export terminal can set a company back nearly $20 billion. The vast majority of these deals in the South — and in the entire country — are located in Louisiana and Texas. The fracking frenzy has made these projects even less expensive to build since U.S.-mined natural gas is abundant and cheap to energize large petrochemical manufacturing plants.

There are now two large LNG export terminals operating in the South, one in Corpus Christi, Texas, and one in Southwest Louisiana on the Sabine Pass. As you can see in the chart, petrochemical projects meeting or exceeding our thresholds peaked in 2015. In fact, last year the 27 petrochemical deals announced in the South were 43 deals off the pace set in 2015.

I don’t believe the drop in deals is the result of less demand for petrochemicals. I think the drop in deals is a labor issue, as new projects wait until another project is completed before they begin building and hiring. There are only so many welders in Texas and Louisiana, and some of the massive projects need thousands of construction workers, which are in short supply everywhere. I think the money is there for these oil, gas and chemical projects, but I don’t think the labor is. So the projects are announced and wait on labor availability. But it’s a certainty that large projects in the petrochemical industry are slowing rapidly.

Yet, there are some sectors that are still thriving

While it is clear that project activity is slowing in the growth sectors of financial services, automotive, building materials and petrochemicals, that is not the case in some other sectors. While fintech has slowed dramatically, other tech sectors are booming. In fact, the day that I am writing this, Apple announced a new $1 billion campus in Austin that will house at least 5,000 engineers, R&D personnel and sales staff. Also in the fall, Amazon announced one of its HQ2s will be built in Arlington County, Va., which will create 25,000 mostly tech jobs. And there’s more. Retailer Lowe’s is hiring 2,000 software engineers in North Carolina in a reboot of the entire company’s tech department. Furthermore, Micron Technologies broke ground on a $3 billion, 1,100-job expansion of its semiconductor plant in Manassas, Va., in the fall 2018 quarter.

So there are no recessionary indicators coming from the tech sector in the South. However, if you recall, that was also the case in the go-go 1990s just prior to the tech industry meltdown in 2000 and 2001. The economic expansion that we have seen the last 10 years is very similar to the economic expansion of the 1990s.

Distribution deals are booming

Another sector that shows no sign of a slowdown is distribution, where Amazon has contributed in a manner not seen before in any industry sector since MCI/WorldCom in the 1990s. In fact, in 25 years, those two companies have announced more projects in the South than any other company. Of course, you might remember how the WorldCom deal turned out. Former WorldCom CEO Bernie Ebbers is still in the big house in Louisiana as a result of that dumpster fire. He will be 87 years old when he is released in 2028.

In the summer 2018 quarter, four Amazon projects announced in the South made our top 10 deals based on job generation. That is unprecedented — four of the top job generating deals in one quarter coming from one company. A fifth, UPS’ 3,000-employee hub near Atlanta, made the top 10 deals in the summer as well. In addition, Amazon chose Alliance Texas Airport in Fort Worth in this fall quarter for a major regional air hub that will create hundreds, if not thousands, of jobs. In short, distribution is a deal juggernaut right now.

As you can see in the chart, distribution has almost tripled its project activity in the South since 2013, and much of that increased activity is coming from one company — Amazon. There have only been two years in the past 25 years in the South when another sector topped automotive in projects meeting or exceeding our thresholds; call centers in 1998 and distribution last year. A steep rise in distribution projects obviously means that consumers are continuing to purchase products at a dizzying pace.

The tariffs are not helping.

When GM cited reasons for closing five North American plants this quarter — four in the U.S. — officials did not directly cite the tariffs that President Trump put on aluminum and steel from foreign sources. GM officials said they were closing the plants because of “changing market conditions and customer preferences.”

Domestic and foreign automakers in the U.S. are seeing their exports, due to retaliatory tariffs by China and other countries, fall on a monthly basis. In short, the worldwide automotive supply chain has been disrupted dramatically by the tariffs on both ends, export and import. And we are seeing economies slow worldwide as a result, including in China and Japan. Japan’s economy actually retracted last quarter. In the case of the automotive industry in particular, tariffs do one thing: fewer automobiles are sold and what is sold costs more. It’s that simple.

Many of the foreign automakers that make vehicles in the Southern Auto Corridor, especially premium brands like BMW, Mercedes-Benz and Volvo, rely greatly on exports. What’s more, in most cases, China is their biggest export customer.

Vehicle sales — depending on the model — have been choppy so far this year. It seems that sales unit success depends on the model, with sedans being a tough sell. Yet, SUVs are as popular as ever in the U.S. This is not good news for the new Volvo plant in Berkeley County, S.C. Volvo officials chose the S60 sedan as the first model to build at the plant, which began full production a few months ago. In a couple of years, the plant will add another line, which will be a SUV.

Because of the uncertainty of the tariffs, Volvo Cars is pivoting its production plans just months after opening its new $1.1 billion assembly plant in South Carolina. It is also slowing hiring at the plant. The Swedish automaker, which is owned by China-based Geely Holding Group, canceled plans to export roughly half the S60 sedans it assembles in South Carolina to China.

Volvo will stop U.S. imports of its popular XC60 SUV from its factory in China. It will also reduce exports of its S90 sedan built in China. These decisions are being made as the automaker finds itself in a pickle regarding President Trump’s tariffs on automobiles. President Trump imposed tariffs of 27.5 percent on Chinese auto imports and in a tit-for-tat move, China’s President Xi Jinping slapped a 40 percent tariff on American-built autos. In 2022, Volvo will assemble its XC90 SUV at its South Carolina plant and will focus on the American market for the S60s it is making there for now.

It is unclear where we stand with these tariffs, and that is exactly what has all these companies spooked. China said in the fall quarter that it is reducing tariffs on imported vehicles from the U.S. from 40 percent to 15 percent. Yet, the situation is incredibly fluid. We will see what happens, or will we? That is the problem. . .the uncertainty is freaking out the automotive industry and other industries. One day it’s this, another day it’s that.

The trade war is also costing Ford. In fact, few U.S. companies have been blindsided by President Trump’s trade war with China and other parts of the world more than Michigan-based Ford. Ford CEO Jim Hackett said in a November story published by Bloomberg that Trump’s tariffs on metal imports will cost the automaker $1 billion in lost profit by the end of 2019. This, despite the fact that Ford was already buying most of its steel and aluminum from U.S. producers.

So why is this administration dismantling the global economic order that we — Republicans, Independents and Democrats — crafted over the last 75 years? Your guess is as good as mine because the president is really messing with a good thing. We are at full employment and there is nothing wrong with a trade deficit, even one that is rising in a trade war.

What we need are more free trade deals, not less. For instance, over the last decade, the Southern Automotive Corridor has lost out on about 10 auto assembly plants to Mexico. The main reason being that Mexico has free trade agreements (FTAs) with 46 countries. We had FTAs with 20 countries, but I am not sure how many we have now.

The last time we set protectionist policies was with the passing of the Tariff Act of 1930, better known as Smoot-Hawley. Even then, 1,028 economists signed a petition asking President Herbert Hoover not to sign the bill. He signed it anyway. What happened? The value of global trade dropped from $4.9 billion in 1930 to $1.8 billion in 1933, and the U.S. fell into an extended depression.

In December, The Wall Street Journal conducted a survey of economists. The survey showed that half of those polled view the trade war with Beijing as the No. 1 risk to the nation’s economy in 2019. About 20 percent polled cited financial market disruptions, and about 12 percent cited a slowdown in business investment as the No. 1 risk to the economy in 2019.

The U.S. economy is about seven months away from breaking the longest economic expansion streak in the nation’s history, set in the 1990s. If we continue expanding through July 2019, the new record will be achieved. However, are we at the inflection point in this expansion where we will see a slowdown in the next few months? The economic development data suggests it just might be that the economy, at least in the South, is curving in a different direction, and that possibly, the threat is self-inflicted.