Another year of monitoring economic development project activity in the South, the world’s third largest economy, clearly shows that this 10-year recovery peaked in 2015 or 2016. SB&D does not judge an economy as an economist does, using real time data such as job creation, GDP, worker productivity and unemployment rates. We look at the economy in just one way — economic development project activity broken down by how many manufacturing and service projects were announced in the region each calendar year.

To judge where the economy is and how it is performing, we count the number of projects meeting or exceeding 200 jobs and/or $30 million in investment announced in the South each year. We use projects submitted by each of the 15 states’ economic development agencies and back that up with announcements published on RandleReport.com. We call it the SB&D 100 in that we publish the top 100 job and investment projects announced the previous calendar year. Ranking the top 100 announced projects creates a threshold for both rankings, and that threshold is the 100th largest project. So, any project of 200 jobs or more and/or $30 million or more in investment up to the 100th largest project earns a state or community five points. If a project lands on either SB&D 100 ranking — jobs or investment — it earns 10 points.

We count the points in each category: rural (less than 50,000 in population); small market (50,000 to 249,999); mid-market (250,000 to 749,999); major market (750,000 to 2.49 million) and mega-market (over 2.5 million in population). Based on points earned, we also rank states. However, while markets are ranked among their peer groups, on the state level, those recognized are the highest point earners based on points per million persons, or points per capita. If we did not rank states on points earned per capita, Texas would win every year based on points alone.

This method of judging the economy makes sense if you think about it. Companies looking to expand production — services or manufacturing — employ experts that can see around corners, see what the economy will be doing in six months, a year, or three years, depending on how long the project will take to complete. Those companies announcing manufacturing deals, such as the Mazda Toyota plant that is being built in Huntsville, Ala., must know as close as possible what the market will be three years out. So, when projects slow, we can see that those same experts believe the economy is slowing as many as three years out. Some service projects, such as financial services, can be up and running in less than six months. However, major manufacturing projects (such as Mazda Toyota) are planned three years prior to the announcement, and completed three years on average after the announcement.

This method of judging the economy makes sense if you think about it. Companies looking to expand production — services or manufacturing — employ experts that can see around corners, see what the economy will be doing in six months, a year, or three years, depending on how long the project will take to complete. Those companies announcing manufacturing deals, such as the Mazda Toyota plant that is being built in Huntsville, Ala., must know as close as possible what the market will be three years out. So, when projects slow, we can see that those same experts believe the economy is slowing as many as three years out. Some service projects, such as financial services, can be up and running in less than six months. However, major manufacturing projects (such as Mazda Toyota) are planned three years prior to the announcement, and completed three years on average after the announcement.

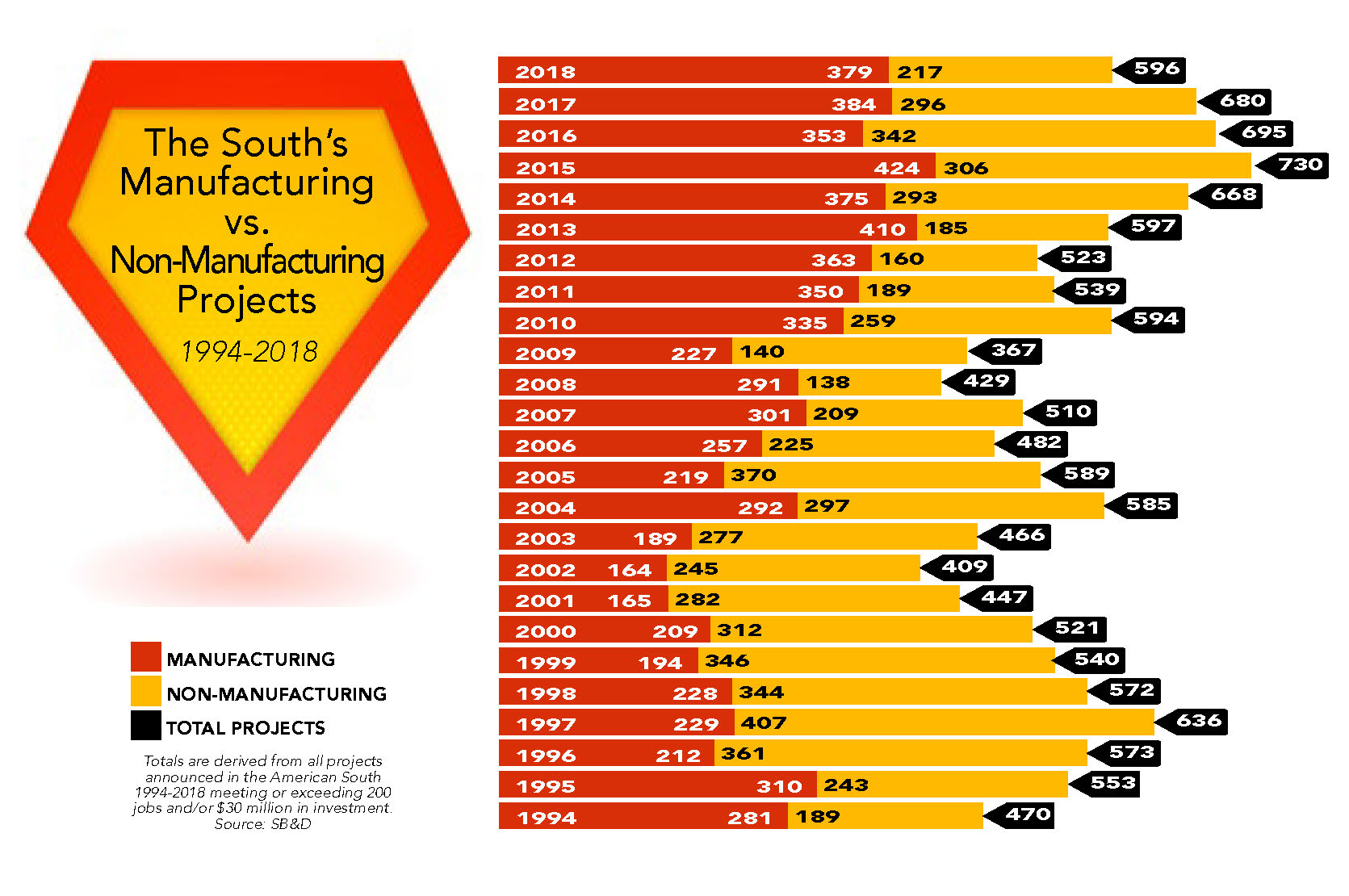

The 2019 SB&D 100 features 596 projects meeting or exceeding our thresholds of 200 jobs and/or $30 million in investment. It’s the first year in five years where the total number of projects did not exceed 600 deals. It’s also the third consecutive year that the total number of projects has fallen from the previous year. As mentioned, the largest number of projects (730) in the history of the SB&D 100 was in 2015 and the second largest (695) number of deals meeting or exceeding our thresholds was in 2016. The total of 596 deals in calendar year 2018 is certainly no bust. The average number of projects meeting or exceeding our thresholds over the last 15 years is 572. So, really, this year’s SB&D 100 is just an average year.

So, while not a bust, compared to 2015, the 2019 SB&D 100 is 134 projects off its record total of 730 announced in 2015 and 84 deals less than last year’s total of 680. Historically, that’s a pretty significant drop in deals announced in the South meeting or exceeding our thresholds.

There are several factors contributing to a dwindling number of projects in the South the last couple of years. For one, we have been at full employment for at least three years. Labor availability is improving as a result of a layoff spike in the first quarter of 2019, but it is still a challenge for employers to find workers to fill jobs. The U.S. labor market is way beyond a skills gap. For three of more years, the labor market has been in a “body gap.” It seems like forever since we haven’t had 6 million jobs or more on average available and unfilled. In other words, it is impossible in today’s labor environment to even put a dent in the number of jobs available.

Yet, we are now in a transition period in this 10-year economic recovery that is longer than any on record. There are signs of economic troubles, some that indicate the end of this economic growth cycle. In the first quarter of this year, layoffs hit their highest level for a first quarter in 10 years according to a report in April from outplacement firm Challenger, Gary & Christmas. Total announced job cuts hit 190,410 in the first quarter, a 10.3 percent increase from the fourth quarter and a 35.6 percent jump from the same period a year ago. The level was the worst period overall since the third quarter of 2015, and the highest level of layoffs for a first quarter since 2009 when the U.S. was still mired in the Great Recession.

There is no question that President Trump’s tariffs are creating uncertainties with many companies. I write “President Trump’s tariffs” because Congress did not approve the added taxes. They were implemented by a single person — President Trump in an executive order. Typically, Congress, not the president, has the authority to raise taxes and tariffs, but the president can do so by declaring special circumstances such as a threat to national security. That is exactly what President Trump did when he raised tariffs on aluminum and steel in 2018.

There is no question that President Trump’s tariffs are creating uncertainties with many companies. I write “President Trump’s tariffs” because Congress did not approve the added taxes. They were implemented by a single person — President Trump in an executive order. Typically, Congress, not the president, has the authority to raise taxes and tariffs, but the president can do so by declaring special circumstances such as a threat to national security. That is exactly what President Trump did when he raised tariffs on aluminum and steel in 2018.

So, here is what President Trump has done so far regarding tariffs according to sources: The Trump tariffs are a series of United States tariffs imposed during the presidency of Donald Trump as part of his economic policy. In January 2018, Trump imposed tariffs on solar panels and washing machines of 30 to 50 percent. In March 2018 he imposed tariffs on steel (25 percent) and aluminum (10 percent) from most countries. On June 1, 2018, this was extended on the European Union, Canada and Mexico. On July 6, 2018, in a separate move aimed at China, the Trump administration set a tariff of 25 percent on 818 categories of goods imported from China worth $50 billion. After extensive trade talks with China ended without an agreement on May 10, 2019, President Trump raised the tariffs on another $200 billion in Chinese imports from 10 percent to 25 percent. China retaliated three days later, announcing new tariffs on $60 billion of American exports.

So, it is easy to surmise that the tariffs have slowed this economy because of uncertainty with the conditions of doing business. U.S.-based companies — both foreign and domestic — cannot move or adjust their supply chains fast enough to follow the President’s orders. Those uncertainties are naturally forcing down the number of projects announced. When a company expands or announces a new project, it needs guarantees that there will be a certain number of buyers for their products or services. The tariffs basically do this: less is sold and what is sold costs more. It’s that simple.

Many CEOs of companies, both large and small, believe that it is unfair for a politician to make the market more difficult to navigate. Trump believed that creating tariffs would force companies to build facilities in the U.S. to get around the taxes. So far, the tariffs have done just the opposite.

In fact, many companies in the South are publicly threatening to move facilities to Mexico and elsewhere to get around the tariffs. Mexico has signed trade agreements with three continents. It has 10 free trade agreements (FTAs) with 45 countries and is a member of the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement. Given the number of Trump tariffs announced, it is impossible to know the number of FTAs the U.S. has with other countries. The situation seems to change every time the wind blows.

In a story published by CNN in May titled, “Trump’s trade war puts Southern Republicans in an awkward spot,” I was quoted along with veterans of economic development in the South, J. Mac Holladay and Michael Olivier. All three of us said essentially that these tariffs have to go, at least at some point. Mac Holladay was quoted in the article, “We’re so interdependent — internationally, economically — there just has to be a way forward that isn’t just always taking an axe.” Olivier said, “We need to get their (China) attention somehow. Maybe this is the way to get their attention. But I don’t know if we can continue this for a long period of time.”

Also in the CNN story, South Carolina Rep. Joe Cunningham said, “I can’t tell you how many folks have come into our office either in Mt. Pleasant (S.C.) or in D.C. just saying they want to know what’s coming ahead. There’s clearly hundreds of millions of dollars in investment projects that have been sidelined or that have been frozen until we figure out where we’re going in this ‘trade war.’ ”

My point in the CNN story was that the tariffs are undercutting the South’s competitiveness with other countries. If you look at the chart on the facing page, notice the years 1996 to 2005. In those years, projects meeting or exceeding our thresholds on the manufacturing side were almost nonexistent, getting beat in big deals by the service sector some years by two-to-one. As President Trump said, those were the years that China and Mexico were indeed stealing our industries. Just check out how many service deals there were compared to manufacturing deals. Services ruled the job-making scene in the South in the late 1990s (think the age of the Internet), while manufacturing was not only struggling to survive in the region, thousands of companies were relocating to China and Mexico. And the lack of manufacturing project activity was happening in the go-go ’90s, the second longest economic expansion in the nation’s history. In short, the U.S., as well as the South, were simply not competitive in the 1990s for manufacturing.

Now look at the years of 2006 to 2018. Manufacturing has dominated services in big economic development projects in the South. Why? That is easily answered. The South essentially became the most competitive region in the world to make something, particularly for U.S. consumption. As manufacturing and labor costs soared in China and Mexico, the cost of doing business in the South actually dropped as the natural gas boom made it incredibly competitive with other countries, even China. So, it was about 2010 that the term “reshoring” was invented. Economics after the Great Recession made it cost-effective to repatriate your plant back to the South, the least expensive place in the largest economy in the world to manufacture goods.

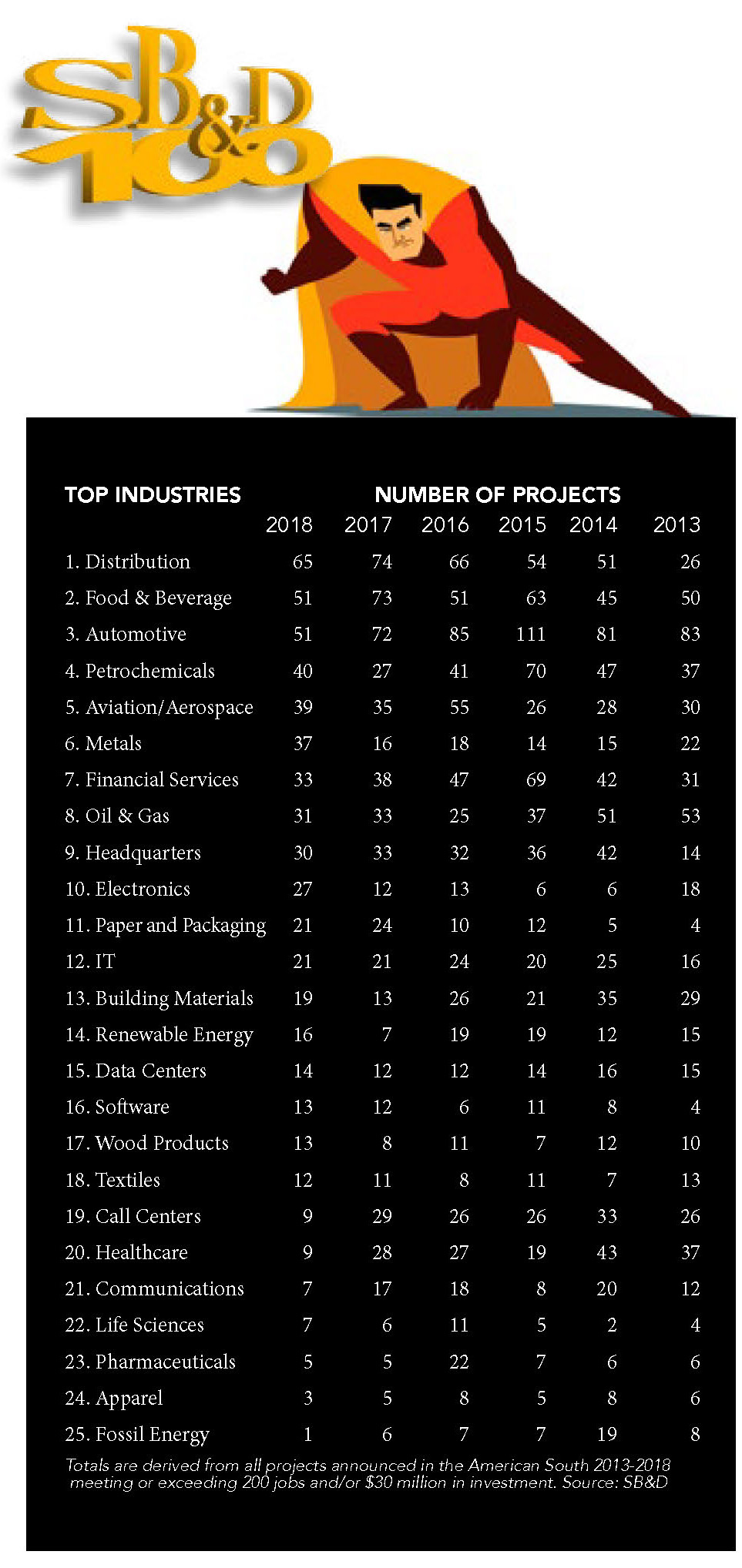

For over 25 years, I have called a good economy “money on the street,” in other words, disposable income is much higher in a growing economy. Therefore, when there is less money “on the street,” the two industry sectors that are affected the most — and this has been the case in every SB&D 100 for 25 years — are automotive and financial services. So, how did those two industry sectors fare in calendar year 2018?

Both the automotive and financial services sectors have essentially crashed compared to the peak of this recovery in 2015. The automotive industry has rung up the largest number of deals in the SB&D 100 in 22 of the 25 years of the SB&D 100 ranking’s existence. In 1998’s total deals, the automotive industry came in second to call centers. Other than that year, automotive led all sectors in big deals every year until 2017 and 2018.

Yes, in the last two years, automotive has played second fiddle to distribution. When the mighty automotive industry in the South, deemed by us in the early 1990s as the Southern Automotive Corridor (go to SouthernAutoCorridor.com), is crashing, that means the region’s economy is not only slowing, it is bordering on contraction.

In 2015, the automotive industry posted 111 projects meeting or exceeding our thresholds of 200 jobs and/or $30 million in investment. That was the largest total of big deals of any sector in SB&D 100 history. In 2018, this year’s SB&D 100 shows that figure was cut in half to 55 deals making our list. However, one of those 2018 projects was the rare greenfield automotive assembly plant, the Mazda Toyota joint project in Huntsville, Ala. Therefore, for automotive, 2018 wasn’t a complete washout.

Yet, the Mazda Toyota deal reminds us of the Toyota project near Tupelo, Miss., that broke ground in 2007, but delayed opening until 2011 because of the Great Recession. I am not saying the Mazda Toyota project in Huntsville will be delayed, but the timing of it is similar to Toyota’s project in Mississippi in that the industry is slowing and fast, just like it did in 2007.

Financial services deals in the South have seen a deeper drop in project activity than automotive in the last three years. In 2015, financials racked up 69 big deals, the second largest total for that sector in 25 years. That total dropped to 33 deals in 2018. The fintech sector was creating tens of thousands of jobs three years ago, particularly in Atlanta, Charlotte and Dallas-Fort Worth. That is no longer the case. Fintech deals have evaporated to almost nothing today. The reason? There is less money “on the street.”

While financials and automotive are showing their first real weaknesses in seven years, there were some sectors that performed marvelously in 2018. Distribution is now king of the deal world in the South, thanks to Amazon and e-commerce. Since MCI/WorldCom’s run of a massive number of economic development deals in the late 1990s, (Remember them and CEO Bernie Ebbers, who is still in jail in Fort Worth, Texas?) never have we seen so many projects coming from one company. Amazon’s announcements in 2018 include seven of the top 15 projects announced in the South, based on job generation. The company also announced the largest project in SB&D 100 history, its HQ2 deal in Arlington County, Va., that will create 25,000 jobs.

While financials and automotive are showing their first real weaknesses in seven years, there were some sectors that performed marvelously in 2018. Distribution is now king of the deal world in the South, thanks to Amazon and e-commerce. Since MCI/WorldCom’s run of a massive number of economic development deals in the late 1990s, (Remember them and CEO Bernie Ebbers, who is still in jail in Fort Worth, Texas?) never have we seen so many projects coming from one company. Amazon’s announcements in 2018 include seven of the top 15 projects announced in the South, based on job generation. The company also announced the largest project in SB&D 100 history, its HQ2 deal in Arlington County, Va., that will create 25,000 jobs.

The positives of this year’s SB&D 100 clearly indicate that people are still buying stuff and by the truckload. This is the second consecutive year that distribution was the No. 1 industry in terms of deals meeting or exceeding our thresholds.

Other industry sectors that did well in the 25th annual SB&D 100 were aviation and aerospace, petrochemicals, electronics and metals. As a result of the tariffs implemented by President Trump on foreign steel and aluminum, those two industries more than doubled their number of big deals posted in 2017. In fact, it was a record year for the metals industry in the South, posting 37 big deals.

Yet, while a few thousand jobs have been saved or created at steel and aluminum factories across the U.S. as a result of the tariffs, tens of thousands of jobs have been lost in other industries that use metals in final assembly, such as the appliances, HVAC and automotive industries. In fact, according to Harvard University, industries using steel outnumber those producing steel 80 to 1.

The 2019 SB&D 100 features 379 manufacturing projects meeting or exceeding our thresholds, and only 217 service deals. The 379 manufacturing deals represent a really strong year. The South’s economy remains incredibly competitive for manufacturing and could be even more so if these pesky tariffs are struck down.

But the 217 service deals (call centers, healthcare, distribution, headquarters, IT) remind us of the collapse of that sector in the Great Recession. It was not manufacturing that cratered in 2007-2009. It was services. Call centers, once a major job generator for rural areas of the South, are essentially non-existent today, turning just nine deals in 2018 compared to 29 in 2017. And healthcare in 2018 also cratered to nine deals from 28 the year before.

Are we near the end of this 10-year growth cycle? The numbers from the 2019 SB&D 100 don’t really indicate clearly that the end is near. The drop in service deals is the most concerning aspect of this year’s ranking. But the fact that the big deal totals have dropped every year over the past three years sure does hint that the economy is transitioning to slower growth. Regardless of the numbers, there will always be plenty of opportunities for companies here in the South, the world’s third largest economy.