The winter quarter is the best of time of the year for any data hound journalist. Economic indicators and opinions from the previous calendar year begin to show up at various media properties, think tanks, the two most important government bureaus that measure the economy and, of course, from the vast number of economists out there releasing their year-end assessments.

The GDP growth in the U.S. economy in 2018 was at 2.9 percent. With that growth rate of 2.9 percent, gross domestic product in 2018 matched 2015 and blew away 2016 (1.6 percent), two years that saw record inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) into the United States. In 2015, foreign companies poured $466 billion into the U.S., and 2016 saw FDI of $457 billion, the two best years in U.S. history.

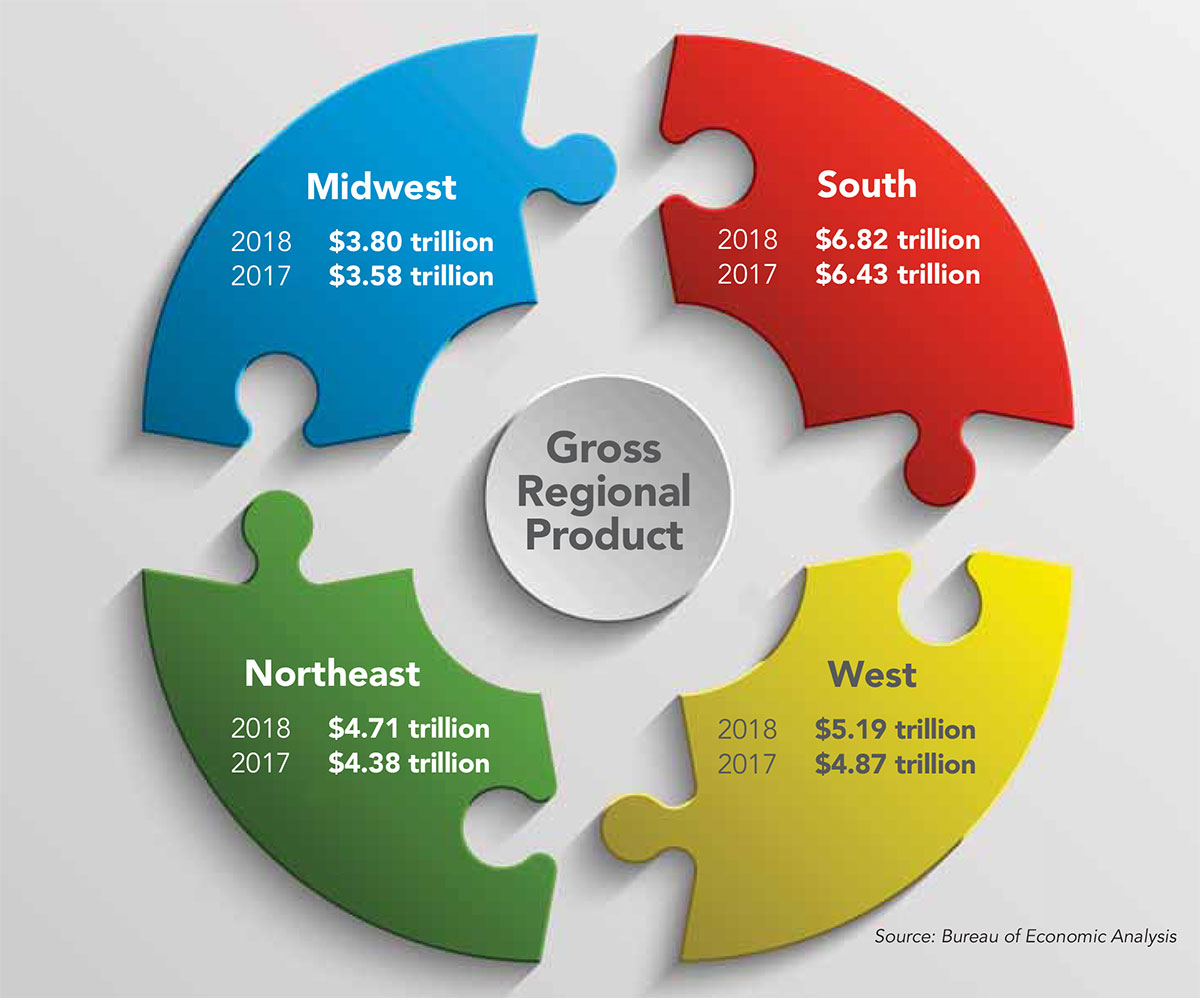

Forty-seven of the 50 states also saw their economies expand in calendar year 2018. In fact, the Bureau of Economic Analysis estimated that in 2018, total U.S. GDP rose above $20 trillion for the first time. The South is leading the way, even pulling away from other regions in what we call “gross regional product,” or GDP tallied in states making up the four U.S. regions — South, West, Northeast and Midwest.

As you can see in the graphic above, GDP in each U.S. region rose in 2018. Furthermore, the 15-state American South is out-pacing the other regions, leading them by a wider margin in gross product than just five years ago. According to the International Monetary Fund, as of the end of 2018, the South’s economy based on GDP is now more than half the size of China’s and remains the third largest economy in the world.

The graphic on page 40 (below) shows the four U.S. regional economies and how they compare to the economies of other countries based on GDP in 2018. These are the 10 largest economies in the world. The South is indeed pulling away from the other U.S. regions.

Yes, the economy remains in decent shape and the job market is the best it has been in decades, sans February when only 20,000 jobs were created. Still, as of March (196,000 jobs), the U.S. has seen 102 consecutive months of job growth. Unemployment has reached its lowest level in 49 years. Workers are scarce, meaning just about everyone who had trouble finding a job in previous years is working, and that includes low-skill and high-skill jobs.

I am unsure whether the paltry 20,000 jobs created in February in the U.S. was the result of the economy slowing or because of demographics, in that there is no one left to fill a job.

Today’s job market reminds me of a remark made by Fred Harris, the former (now retired) SVP of Economic Development of the Nashville Chamber of Commerce, in 1999, at the tail end of the longest economic recovery on record. Fred said, “Michael, I’ve never seen anything like it in the decades of working at the chamber. We have people here in Nashville who are working that don’t even want to work.”

If this economy remains a 10-year spectacle, what’s keeping it from growing at 4 percent?

While the U.S. economy still has legs in this 10-year recovery period with a growth rate of about 3 percent, 2018 should have seen a GDP growth rate of at least 4 percent, possibly higher. There are three primary issues holding back economic growth in the U.S. and in the South — demography, a significant drop in foreign direct investment and trade wars.

The first issue holding back the economy and keeping GDP growth at under 3 percent is that we seemingly have over 7 million job openings every month and no more than 300,000 people taking those jobs per month. But in reality, the average monthly job gains are right at 180,000 per month over the last year, so no more than 2.2 million jobs were gained last year.

The February jobs report shocked just about everyone, including many economists, with only 20,000 jobs gained in the U.S. But, given the long-term demographics, those 20,000 jobs are not surprising. The Federal Reserve has stated for three years that the economy will continue to grow at 50,000 jobs created per month. Get used to those numbers and say goodbye to 300,000 jobs created in consecutive months. Sure, there might be an outlier when 300,000 jobs are created, but that will be rare for years to come.

In today’s economy, we have over 7 million jobs that can’t be filled in any given year, and that has been the case for three or four years now. This labor squeeze is without question holding back growth in this country. Imagine the effect on the economy if those 7.5 million jobs that are available now were filled in one year, instead of rolling over each year? If that materialized, the U.S. in that year would have at least a 4 percent, possibly 5 percent growth in its economy by my estimations. The question you might be asking now is, “Why can’t those 7.5 million jobs that seem to be eternally available be filled?”

Some will point out that, on paper, there are about 6 million unemployed people in the U.S., with about 7.5 million jobs available. Let me tell you with great confidence, those figures are way beyond full employment, even more so than the late 1990s, the last time we experienced full employment.

If you maintain the simple fact that there are 6 million available workers in the U.S. to fill 7.5 million available jobs, then you have a narrow view of the situation. An unemployed person is anyone age 16 to 64 that is not working, according to the feds. How many of those are students, disabled, family caretakers, retirees, mentally ill or drug addicted? It is estimated that about 5 million of those 6 million people have a reason not to work as a result of my calculations based on tons of data processed. So, essentially, the U.S. currently has about 1 million (or less) unemployed, hirable people to fill those 7 million jobs.

The reasons why we can’t fill the jobs that are available are not complicated, yet, they are not well known. I have written about the factors ad nauseam for more than four years. But since we have new readers each issue, it’s probably best to repeat the demographic ingredients holding back economic advancement, not only in this presidential cycle, but in all cycles that go back to Clinton and yes, even Reagan.

For one, we are in a baby bust. The U.S. population hasn’t grown above 1 percent since 2002. In short, this generation of people from about age 21 to 41 is just not having children at the same rates we have seen historically. In fact, last year the U.S. saw its lowest fertility rate since the Great Depression at 60 births per 1,000 women of child-bearing age of 15 to 44.

For decades after World War II, the U.S. could count on an average of 200,000 people turning working age (16) each month. The current 17-year baby bust has brought that figure down to an average of 70,000 people turning working age each month in the last four years. That is expected to drop to 50,000 people turning working age per month by 2028 according to the Census Bureau. This is a systemic problem. In fact, low birth rates are the greatest threat to our economy and our society at large. Some economists based in other countries have predicted that if they cannot replace current workers, they are living in a “dying nation.”

The biggest challenge this country is facing now, and for many years or decades to come, is that too few people are being born and too many people are aging out of the workforce. In other words, we cannot replace those aging out the workforce. We’re not even close to being able to fill the number of jobs currently available.

So, as a society, what does this mean? It means we cannot pay for future benefits such as Social Security and social medical programs like Medicaid. Why? With fewer workers there are less taxes collected. Social benefits in this country are paid generationally. For example, taxes on my wages are currently paying for my parents’ benefits. If there are fewer workers, how are our benefits or our childrens’ benefits going to be paid?

Before he retired from politics, Speaker Paul Ryan said this: “We have something like a 90 percent increase in the retirement population, but only a 19 percent increase in the working population in America. So what do we have to do? Be smarter, more efficient, more technology. . .still going to need more people.”

Is the answer having more children? There is an easier solution.

President Trump said in this year’s State of the Union address that “legal immigrants enrich our nation and strengthen our society in countless ways. I want people to come into our country in the largest numbers ever, but they have to come in legally.” This statement and Trump’s apparent pullback on immigration was a shock to immigration hardliners in his base. Let’s hope he and Congress act on those words, because solving the full employment and low fertility rate dilemma may be as simple as increasing legal immigration.

Yet, the facts are this: Legal and illegal immigration has fallen in the last decade, mainly due to a decrease in the number of illegal immigrants coming to the U.S., and fewer visas being granted to those wanting to legally migrate over the last two years. The decrease in the growth of the unauthorized immigrant population can partly be attributed to the fact that more Mexican immigrants are leaving the U.S. than coming in, according to the Pew Research Center in a report in November 2018.

However, since that report was released, it should be noted that in the last four months or so, undocumented immigrants from Central America have crossed the border in much larger numbers than late last year. In fact, the numbers are so large (about 75,000 a month) that authorities on the border are currently overwhelmed.

During President Trump’s first two years, apprehensions at the border averaged about 32,000 per month. During President Obama’s two terms, the average number of apprehensions at the border per month was 34,000. The monthly average under Bush was 81,000 apprehensions per month. So, outside of the last four months, there have been fewer immigrants seeking asylum in the United States compared to the 2000s.

So, the first factor holding back the economy is simply a lack of labor. . .no, let’s simplify that to a lack of people, period. It’s no longer a skills gap. Everyone who has skills has a job. Today there is a body gap, and in light of the low birthrate, the only way the current workforce is going to be replaced is by increasing legal immigration by millions each year.

Slow, if not negative, population growth is happening all over the developed world. It’s happening in Europe, Asia and Japan. Even China’s fertility rate is way down. But, so far, only Japan with its intern program for Chinese workers is doing something about it. We certainly are not, yet. If you can’t replace your workforce, there is only one thing to do —

accept slower economic growth.

Now, illegal immigration is a political matter. I realize that some are very hostile to illegal immigrants because our president is, even though almost all of us —

including President Trump — benefit from their work and almost all of us have paid an undocumented worker at one time or another. Here are a few examples of how important illegal immigrants are to the nation’s economy.

Number one, they perform jobs Americans will not do, such as picking fruits and vegetables and other farm work. There isn’t a single farmer in America —

most of which are getting hammered by tariffs issued by China — that has ever said, “We need less undocumented workers.” I realize that is political. But the argument that undocumented workers “steal” from America through social programs is laughable. Most of them pay taxes for social services they can never use, including Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid.

Also, we have all heard about the skills gap crisis. It’s really not a crisis. Companies love to say they can’t find “skilled labor.” For some, this is an excuse for hiring levels that do not meet the thresholds outlined in their incentive contracts. Why don’t these companies teach the skills their new workers need once they are hired? If you are trying to fill 7.5 million available jobs at a rate of 20,000 per month like that found in the February jobs report, you’re not dealing with a skills gap, you’re dealing with a body gap.

No “skills gap crisis” for these states. . .

According to Mississippi Gov. Phil Bryant, workforce is the No. 1 decision location driver for today’s industries, and the state has made funding for workforce training a priority. Pictured is East Mississippi Community College’s new Communiversity, located in Lowndes County.

Louisiana’s FastStart program has been recognized as one of the nation’s top state workforce training programs. Launched in 2008, it has trained 26,000 workers for 175 companies. Here, the Software Engineering Apprentice Program is producing talent for the GE Digital Technology Center in New Orleans and other tech employers there.

The Kentucky Federation for Advanced Manufacturing Education (KY FAME) is an apprenticeship-style educational program. Another state program, the Kentucky Work Ready Community certification program, is a measure of a county’s workforce quality. More than 70 percent of Kentucky’s counties are Work Ready or Work Ready in Progress. One hundred percent of Kentucky’s counties have begun the process to become Work Ready.

And the final example: President Trump wants to build a wall on our Southern border with Mexico. I have half-jokingly said many times, “Yes, we need to build a wall to keep our labor, legal or not, in this country.” I say this because President Trump is going to need illegal immigrants to build that wall. . .half of the construction workers in Texas are undocumented.

The United States is home to the largest amount of foreign direct investment in the world. Yes, much more than China and any country in Europe. Not only is the U.S. the largest recipient of FDI in the world, it is also the largest direct investor abroad.

Many people believe that U.S.-based multinational companies opening plants in offshore countries is a slap in the face to American workers. Most economists would aggressively argue that point (as do I), in that 74 percent of the accumulated U.S. outward bound FDI last year was spent in high-income developed countries, such as the U.K., Germany, Japan, etc., where manufacturers plan to sell their goods, not low-income undeveloped countries.

The trend since the recession ended in 2009 for not only U.S.-owned manufacturers and service providers, but foreign-owned as well, is to make it and sell it in the country (or nearby) where your buyers are. Or “make it where you sell it,” a phrase used in a cover story SB&D ran in 2010 about reshoring.

This economic model of “make it where you sell it” has transformed U.S. manufacturing as thousands of manufacturers have repatriated jobs and plants to this country because it is economically feasible to do so. Sure, there are plenty of plants offshore that make things for U.S. consumption. But the larger items, such as cars, tires, construction equipment and say, large pipe used in the oil and gas industry, are best made in the country where they are sold. It’s just economics, considering the cost of shipping and other factors.

The reshoring event that began in 2010 remains a key and favorable component in the U.S. economy. Manufacturing jobs began their turnaround after the recession simply because the U.S. became more competitive, specifically in energy costs for manufacturing plant loads. It should be noted that around 2010, the fracking frenzy began in earnest, putting the U.S. in an enviable position to offer energy costs no other country could offer. That advantage remains today, and the export of our U.S.-mined energy has never been higher. Our newly cost-competitive economy has led to hundreds of thousands of new manufacturing jobs since the recession ended. In fact, from July 2017 to July 2018, more than 327,000 net new manufacturing jobs were created in the U.S., the best 12-month stretch in 23 years.

Offshoring was an issue when the U.S. could not compete with China and elsewhere from the late 1980s through the 2000s. Reshoring was new to me until I read several economic reports on the subject, specifically a report done by the Boston Consulting Group in 2011 titled “Made in America Again: Why Manufacturing Will Return to the U.S.” That may still be the most important economic development report (especially for the South) ever written. Because of its low cost of operating a business, combined with the fact the region was suddenly swimming in natural gas, the “Made in America, Again,” authors — specifically Hal Sirkin — predicted that in just a few years, manufacturing plants in the South would be cheaper to operate than those in China. That has happened.

FDI is faltering in the U.S., and the political atmosphere and tariffs are the main reasons.

FDI is faltering in the U.S., and the political atmosphere and tariffs are the main reasons.While reshoring or repatriating manufacturing facilities back to the South is indeed a trend, foreign direct investment in the U.S. has fallen on hard times after setting investment records in 2015 and 2016, as mentioned in the introduction of this story. President Trump’s tariffs (I write “President Trump’s tariffs” because the taxes were born by executive order and not by a bill passed by Congress) have made investing in the U.S. by foreign companies a risk.

President Trump envisioned the tariffs would, in part, attract foreign investment because if you build a product in the U.S. it is immune to the levies, which are essentially a tax on products that are imported here. But so far, the exact opposite has happened when it comes to inflows of foreign companies investing in the U.S. In other words, what has happened historically when the U.S. puts in place protectionism policies is that less is sold, and what is sold costs more. Tariffs work for some industry sectors, but the vast majority get hammered. And that is exactly what has happened in the first year of Trump’s tariffs.

FDI inflows into the United States (FDIUS) dropped to $275 billion in calendar year 2017. That is down by 40 percent compared to 2016 and 2015. And FDIUS inflows in 2018, which are not available yet, look much worse than 2017. Why? In the second quarter of 2018, FDI in the U.S. was negative $8.2 billion, meaning a divestment, or foreign firms selling off their U.S. subsidiaries.

Q2 2018 is one of only six quarters since 1982 that the U.S. has seen net divestment in FDIUS. The United Nations Conference on Trade Development reported at the end of 2018 that FDIUS fell by 40 percent for the first half of 2018 compared to 2017, which saw a 40 percent drop from 2016. This is a massive issue for the economy considering the fact that the 15-state American South in some years captures over 55 percent of foreign direct investment in this country.

The South’s economy is built for FDI. The region boasts more ports than any other region by a wide margin. The South has the lowest union rate of any other U.S. region by a wide margin, and countries like Japan, Germany, the United Kingdom, Belgium, South Korea, The Netherlands and Canada have made massive investments in the region and continue to do so, just at a lower pace.

As a result of the tariffs, investment from China has essentially ceased at a time when the Chinese were the fastest growing country in inflows into the United States just two years ago. The impact of the tariffs are real and in some cases, very worrisome. For example, Chinese foreign direct investment in the United States in 2016 was $46 billion. That figure dropped to $30 billion in 2017. In 2018, after the tariffs were enacted by the U.S., then by the Chinese in retaliation, China’s investment in the U.S. dropped to just $4.8 billion, or 90 percent less than two years earlier.

Why is foreign direct investment so important to the South and the U.S.? Since the manufacturing sector began adding jobs in 2010 and every year since at a rate not seen since the 1990s, two-thirds of those new manufacturing jobs were created by foreign-owned companies. Think about that. Since the recession ended, the U.S. has added more than 1 million manufacturing jobs and most of those jobs were created by foreign-owned manufacturers. Those foreign companies pay wages, on average, 24 percent higher than their domestic counterparts.

Why is foreign direct investment so important to the South and the U.S.? Since the manufacturing sector began adding jobs in 2010 and every year since at a rate not seen since the 1990s, two-thirds of those new manufacturing jobs were created by foreign-owned companies. Think about that. Since the recession ended, the U.S. has added more than 1 million manufacturing jobs and most of those jobs were created by foreign-owned manufacturers. Those foreign companies pay wages, on average, 24 percent higher than their domestic counterparts.

Specifically, here is what President Trump is trying to do with the tariffs with China: The trade talks underway between the U.S. and China are centered on providing better access in China for U.S.-based companies, enforcement of intellectual property protections and an end to industrial subsidies. Good luck with the subsidies, which are not subsidies at all, but incentives in exchange for hundreds of millions in investment and hundreds of thousands of jobs. A subsidy is a bailout (such as GM in 2009), which creates zero jobs initially. (Editor’s note: You writers who call incentives “subsidies,” please refrain from doing so and explain the difference between the two.)

By the time this issue is mailed, President Trump and his trade officials may have struck a trade deal with China. In the meantime, President Trump’s year-long trade war has helped widen the trade deficit he has fought so hard to reduce. At the end of 2018, America’s trade deficit in goods with other countries rose to its highest level in history. The U.S. imported a record amount of goods, which increased the deficit to $891.3 billion.

Trump’s trade war with China is indeed expanding the deficit. The Chinese economy has been slowed significantly by the tariffs Trump has levied on Beijing. In fact, it has slowed to the point that it has hurt our exports not only to China, but Europe as well. In December 2018, U.S. exports declined nearly 50 percent compared to December 2017. Now, it should be noted that exports in 2018 surpassed 2017 by a small margin. Yet, after nearly a year since imposition of the tariffs, is the drop in December exports the beginning of a trend?

Also contributing to the trade deficit setting all-time records was Trump’s $1.5 trillion tax cut. The tax cuts are now being financed by increased government borrowing. This has increased U.S. debt to $21.5 trillion at the end of fiscal 2018. Many economists warned President Trump that the tax cut would both increase the national debt as well as increase the trade deficit. Remember, all countries generate trade deficits when they consume more goods than they generate at home. The tax cuts gave some Americans extra cash. What did they do with that extra cash? Many of them bought more imported goods.

There are some winners in Trump’s trade wars, not many, but there are a few. Steel mills have prospered dramatically, not in job generation, but in profits. Companies like Charlotte-based Nucor are setting revenue records. When Trump put tariffs on foreign-made steel and aluminum, domestic steel manufactures saw a strategic opening and they pounced on it. For the most part, they raised the price of steel.

But even with the tariffs in place, few jobs have been created at steel plants in the U.S. Technology advances at those plants have created massive job losses in the sector, much like that in other industry sectors. In 1980, there were over 500,000 workers at steel plants in the United States. Today, even after the Trump tariffs on foreign-made metals, there are about 150,000 jobs at steel plants, with a gain of about 4,000 jobs last year.

On the other hand, we have tens of thousands of manufacturers who finish metal products, such as HVAC, appliance, auto parts manufacturers and automotive OEMs. The number of steel plants in this country is nothing compared to those manufacturers that use steel. These companies suddenly saw their costs for steel and aluminum skyrocket. Not only that, many of the U.S.-based steel suppliers cannot even come close to producing the specialty steels that American manufacturers need from foreign suppliers. So, many steel product manufacturers must still rely on foreign suppliers at a tax penalty of 25 percent.

After some research, I discovered a report released in the fall of 2018 by the Cato Institute titled, “Here Are 202 Companies Hurt by Trump’s Tariffs.” This article is the best example I have seen of the effect of Trump’s tariffs on farmers, those who work with metals and just about every industry imaginable. The sizes of the companies that are hurt by these tariffs are meaningless, because the damage is relative and widespread to all.

After some research, I discovered a report released in the fall of 2018 by the Cato Institute titled, “Here Are 202 Companies Hurt by Trump’s Tariffs.” This article is the best example I have seen of the effect of Trump’s tariffs on farmers, those who work with metals and just about every industry imaginable. The sizes of the companies that are hurt by these tariffs are meaningless, because the damage is relative and widespread to all.

The Cato story is written by Scott Lincicome, who is a senior policy adviser at “Republicans Fighting Tariffs,” an international trade attorney, Cato Institute adjunct scholar and adjunct professor at Duke University Law School. It profiles very accurately 202 companies harmed by these tariffs.

The introduction to the Cato story: “The debate over tariffs has mostly emphasized their impact on economic growth and jobs, which overlooks specific stories of suffering caused by President Donald Trump’s trade war. Below are more than 200 examples of the damage done by Trump’s tariffs, aggregated with (by) Republicans Fighting Tariffs. The victims and their stories differ, but the catalyst is the same.”

The Cato Institute’s report included those bruised by both the U.S. tariffs on imports and retaliatory tariffs on U.S. exports. We have hand-picked 21 examples of the 202 that Cato profiled in its study. Go to Cato’s report to read about the other 181 companies profiled.

1. Fluor: “The oil and gas company gets some components for its plants from Chinese manufacturers. Its major methanol project in Louisiana could be delayed or canceled due to increased costs and uncertainty.”

2. Arrow Fasteners: “The staple manufacturer cannot pass along tariff-related increases in input costs to customers because they would just turn to foreign competitors. ‘We’re stuck,’ says the owner.”

3. General Motors: “The car maker, which cut its earnings forecast for the year because of surging prices for steel and aluminum caused by tariffs, is considering cutting U.S. jobs.” (GM later closed four plants in the U.S. and one in Canada.)

4. Batesville Tool & Die: “The Indiana company may be forced to shift some production to a plant in Mexico in response to higher steel prices caused by tariffs.”

5. CaseLabs: “The California PC case maker has been forced into bankruptcy and liquidation because of Trump’s tariffs, which raised its costs by almost 80 percent.”

6. BMW: “The car maker says tariffs could lead to ‘negative effects on investment and employment in the United States.’ ” (Note: BMW’s only U.S. plant, and its largest plant in the world, is in Greer, S.C., where it employs over 8,000 workers.)

7. Boeing: “The aircraft maker’s stock price cratered (in the fall and then later in the winter) because of worries that tariffs will cause China to shift purchases to Airbus.” (Note: Boeing operates two final assembly aircraft facilities in the U.S. in Washington and its 787 Dreamliner plant that houses over 10,000 employees in North Charleston, S.C.)

8. Harley-Davidson: “The motorcycle manufacturer cut its profit margin forecast for the year due to tariffs, which are forcing it to move some production overseas.” (Harley closed its Kansas City plant in 2018 and the property is up for sale.)

9. Infinity 8: “The California exporter’s shipments of cherries to China fell from 10,000 cartons in 2017 to 240 in 2018 because of retaliatory tariffs. In 2017, it shipped 76,410 cartons of Valencia oranges to Shanghai. In 2018 it shipped 3,240. In 2017 it shipped 44,036 cartons of plums to Shanghai. In 2018 it shipped 170.”

10. General Electric: “The U.S. conglomerate, which faces $400 million a year in tariff-induced costs, is considering adjusting its supply chain to mitigate the effects.”

11. Alcoa: “The aluminum-product manufacturer cut its profit forecast ranges by $500 million, citing tariffs on aluminum it imports from Canada.”

12. Little Bay Lobster Co.: “The New Hampshire company had a big market in China that has dried up because of retaliatory tariffs. It doesn’t know how long it can pay its 75 employees, who aren’t working.”

13. Hyundai: “Tariffs will push up production costs at the car maker’s Alabama plant by 10 percent a year.”

14. Kia: “Tariffs will harm the car maker’s U.S. operations (its only U.S. plant is in West Point, Ga.) and jeopardize plans for additional U.S. investments.”

15. Caterpillar: “The tractor company faces $200 million in tariff-related costs in the second half of 2018, forcing it to raise prices.”

16. Ryan Mickelson: “ ‘The farm economy is not good right now at all,’ the Iowa farmer says, ‘and if something doesn’t change, there is going to be a lot of farmers going bankrupt. Something has to change, and something’s got to change fast. Trump promised and said nothing is going to happen to us farmers, but since this came out and tariffs took effect we’ve seen nothing but a dive in the markets.’ “ (NOTE: A Wall Street Journal story published in February included in part, “A wave of bankruptcies is sweeping the U.S. Farm Belt as trade disputes add pain to the low commodity prices that have been grinding down American farmers for years.”)

17. Lucerne International: “The Michigan auto supply producer says tariffs threaten the life of the company, the livelihood of its employees, and an intricate auto supply chain that creates hundreds of thousands of U.S. jobs.”

18. Moog: “The musical instrument maker may cut jobs or move operations out of the country because tariffs will make it too expensive to do business in the U.S.”

19. Anthony Rinald: “ ‘The margin of profit is low, real low,’ the Pennsylvania farmer says. ‘It’s borderline if we’re going to make it or not.’ ”

20. Toyota: “The car maker, which faces nearly $100 million in tariff-related cost increases per year, may stop importing some vehicles into the U.S. because of proposed U.S. tariffs.”

21. Volvo: “The car maker is raising prices to offset the costs of the trade war.” (NOTE: Swedish-based, Chinese-owned Volvo’s new plant that currently assembles the S60 sedan near Charleston, S.C., will not export its cars to China as a result of the tariffs. The $1.1 billion plant was built to export half its cars to China.)

21. Volvo: “The car maker is raising prices to offset the costs of the trade war.” (NOTE: Swedish-based, Chinese-owned Volvo’s new plant that currently assembles the S60 sedan near Charleston, S.C., will not export its cars to China as a result of the tariffs. The $1.1 billion plant was built to export half its cars to China.)

In reading the responses from the owners or spokespersons for the companies cited, you can see a theme. No. 1: they are all struggling as a result of higher materials costs. No. 2: many of the companies are being shut out of China as a result of the retaliatory tariffs. No. 3: many will ditch domestic suppliers for foreign ones, whose products are still less expensive even though they are taxed. No. 4: some expect to relocate their plants to other countries as a result of the tariffs. No. 5: just about every company that can survive these tariffs is passing the increased costs to you, the consumer. No. 6: many of these businesses are having to reinvent their supply chains (many of which have been in place for decades) not only to stay profitable, but to survive. And lastly, because of U.S. tariffs on Chinese goods, many U.S. companies who make products for U.S. consumption in China are considering moving their plants to Cambodia and other Asian countries just to bypass Trump’s tariffs on China.

These tariffs, both from the U.S., China, Europe, Canada and elsewhere, are robbing the former free trade world and its economic base. The examples from the Cato Institute report are from U.S. companies or foreign affiliates. What do you think Chinese companies are going through? It’s probably worse.

President Trump (again, not Congress) imposed steel and aluminum tariffs on March 1, 2018. Trump announced his intention to impose a 25 percent tariff on steel and a 10 percent tariff on aluminum imports. In a tweet the next day, Trump asserted, “Trade wars are good, and easy to win.”

The 21 examples we published in this story of the 202 examples published by the Cato Institute show one thing: the vast majority of companies are losing, not “winning,” in this trade war, and they come from all sectors. And don’t forget, Cato’s story was written late last year, so those companies are in worse shape now than they were then simply because they have had about five more months of exposure to the tariffs.

An escalation of additional tariffs, over and beyond what is in place now, will rock the U.S. economy, and most likely throw it into recession. If President Trump, as he has threatened to do, imposes tariffs on cars and car parts that are imported from Asia and Europe to the U.S., it won’t be pretty.

Jim Lentz, CEO of Toyota North America, was quoted in a story published by many media properties in mid-February, saying, “I think it makes it difficult. . . because it’s going to impact the overall industry.” Lentz, who is now operating out of Toyota’s brand new North American headquarters in Plano, Texas, announced $750 in million investments in plants in Alabama, Tennessee, Missouri and other states in mid-February. He also said he could cancel those investments if Trump put tariffs on foreign cars and parts. Toyota and Mazda are also building a 4,000-employee plant in Huntsville, Ala. If Trump places tariffs on foreign automobiles and car parts, I believe the odds that Toyota and Mazda will finish the plant are 50-50.

Jim Lentz, CEO of Toyota North America, was quoted in a story published by many media properties in mid-February, saying, “I think it makes it difficult. . . because it’s going to impact the overall industry.” Lentz, who is now operating out of Toyota’s brand new North American headquarters in Plano, Texas, announced $750 in million investments in plants in Alabama, Tennessee, Missouri and other states in mid-February. He also said he could cancel those investments if Trump put tariffs on foreign cars and parts. Toyota and Mazda are also building a 4,000-employee plant in Huntsville, Ala. If Trump places tariffs on foreign automobiles and car parts, I believe the odds that Toyota and Mazda will finish the plant are 50-50.

Few understand the depth of the auto industry in the South and in the U.S. It is by far the largest industry in the South (go to SouthernAutoCorridor.com) and has been for more than 25 years. In those 25 years, the Southern Auto Corridor has captured more than 85 percent of all new assembly plants announced in the U.S.

The country that has captured the rest of the new North American auto assembly plants — and we are talking about a significant number of assembly plants— has one thing the U.S. doesn’t have. Mexico has free trade agreements with 45 countries. Our FTAs are reduced in number.

I will repeat what I always say about tariffs, “Less is sold, and what is sold costs more.” In other words, nobody wins in a trade war. We all lose. We all sell less and what we sell costs our customers more. There are no winners. And the data is telling us more each day that the U.S. and China, in self-inflicted fashion, are taking each other’s economies down. All the while, the China versus U.S. trade war is slowing the entire global economy.

So, what are the three factors holding back a good economy? (1) Increase legal immigration to help fill the seemingly endless 7.5 million jobs that are available each year. (2) End the tariffs to bring inflows of FDI to levels seen in 2015 and 2016. (3) End these destructive tariffs (both U.S. tariffs and retaliatory tariffs) and go back to the free trade system, ading more countries to our original FTAs to get our small, medium and large companies back on their feet. See, without politics, the problems we have with our economy are easy fixes. But factor in politics and these are three not-so-easy pieces.