With great pride, leaders in the American South have promoted the region to industry in many ways. Over the last 100 years, the South’s most often used sales pitch to business and industry is the fact that it costs less to operate a business in the South than the other three U.S. regions — the West, the Midwest and the Northeast. To be the low-cost leader in the largest economy in the world is a great advantage when it comes to job generation, and is certainly a major factor behind the South’s population surging past the Midwest and the Northeast’s populations combined.

Sixty years ago, each of the three regions had about the same population. But the decades-long migration to the South has had an effect. Last year, more than 1.4 million people migrated to the South, and most of those were from the Midwest and Northeast.

California is also a source of new Southerners, particularly new Texans. Toyota, the world’s top selling automaker, is in the process of moving its 4,000-employee North American headquarters from California to Plano, Texas. Once settled, the company will enjoy a number of cost advantages there compared to California. In fact, according to Toyota execs, housing costs are one of the main reasons the company is relocating its base to Texas. Housing is incredibly expensive in California and, considering many of the company’s employees couldn’t afford to live within a short drive of the current base of operations in Torrance, Calif., it was certainly a problem. The median home price in Torrance is $723,800. The median home price in Plano, Texas is $278,750.

In January, Toyota CEO Jim Lentz said that up to 75 percent of the 4,000 California employees have indicated they will relocate with the company to the new 2-million-square-foot headquarters being built in Plano. And you can bet that Toyota won’t ask its employees to take a pay cut for moving, even though it will cost them much less to live in North Texas.

Toyota’s move will be a huge boost to one of the most powerful economies in the U.S. The Dallas-Fort Worth region, where Plano is located, is one of the fastest growing metro regions in the world. With the capture of Toyota’s headquarters, another $400 million in wages each year will be flowing through North Texas’ housing, entertainment, financial services and retail sectors.

WAGES

Few people outside of it understand the practice of economic development. However, wages are something that everyone understands, because most everyone earns a wage. I often tell people who are charged with explaining how economic development works to focus on the wages a single project will inject into a community. For example, the BMW plant in South Carolina generates about $700 million in wages for the Upstate region each year, not including the automaker’s suppliers. Include them and the wages are upwards of $1.7 billion a year for a single project. The plant has been operating since 1994, and it will continue to roll out SUVs for many years to come, meaning the incentives paid to BMW are a pittance compared to the wages generated over the course of, say, the 75-year lifespan of the plant.

In the spring quarter of 2014, the U.S. finally generated the number of jobs lost in the Great Recession — 8.7 million — that were on payrolls at the start of the downturn in December 2007. The current unemployment rate is 4.9 percent nationwide and 5.3 percent in the South. Both figures suggest we are nearing full employment and should achieve that lofty and rare status this year. However, some states have not recovered all of the jobs lost in the recession, almost seven years after it officially ended. And the slow, 2-percent-on-average growth rate during the recovery is occurring in the fourth-longest economic expansion in the U.S. post World War II.

In the spring quarter of 2014, the U.S. finally generated the number of jobs lost in the Great Recession — 8.7 million — that were on payrolls at the start of the downturn in December 2007. The current unemployment rate is 4.9 percent nationwide and 5.3 percent in the South. Both figures suggest we are nearing full employment and should achieve that lofty and rare status this year. However, some states have not recovered all of the jobs lost in the recession, almost seven years after it officially ended. And the slow, 2-percent-on-average growth rate during the recovery is occurring in the fourth-longest economic expansion in the U.S. post World War II.

By the numbers, the economy looks pretty good, as it has for five years now. In terms of economic development in the South, project numbers are excellent as well. We won’t have final numbers for 2015 for a few more weeks, but from the five-year period from 2010 to 2014, there was an average of 584 projects announced in the South meeting or exceeding 200 jobs and/or $30 million in investment. That average beat the previous five-year record of 1995 to 1999, when the average was 575 projects announced each year. In fact, in calendar year 2014, there were 668 projects meeting or exceeding those thresholds. That beat the previous record of 636 projects announced of 200 jobs and/or $30 million or more in investment announced in 1997.

While there have been signs of an economic slowdown of late, with the stock market dropping significantly at the start of the year and the oil sector collapsing, make note of this: never in the history of the U.S. economy has the country gone into a recession while it was creating jobs. Job creation in the past two or three years has been fairly consistent, even robust at times, and as mentioned, we should reach full employment sometime this year barring some kind of economic disaster.

Since 2010, as mentioned, this is one of the nation’s longest economic expansions. That being the case, then, why doesn’t it feel like it? This expansion post-Great Recession is already two-thirds of the length of the one from 1991 to 2001. Yes, we all remember the go-go 1990s. Now that was a period of unprecedented economic growth, particularly the last five years of that decade, and it certainly felt like it.

So, why doesn’t this economic expansion “feel” like the expansion of late 1990s when economic development projects today are setting records in the South, and the nation is on the cusp of full employment? Two things come to mind: No. 1, there was a boatload of debt created in the Great Recession. For those who didn’t bankrupt, much of their disposable income over the last several years has gone to paying off that debt. Much more important to the subject, however, is the No. 2 reason why this expansion doesn’t feel like others: wages have seen pathetic growth since the recovery began in its first full year in 2010.

So, why doesn’t this economic expansion “feel” like the expansion of late 1990s when economic development projects today are setting records in the South, and the nation is on the cusp of full employment? Two things come to mind: No. 1, there was a boatload of debt created in the Great Recession. For those who didn’t bankrupt, much of their disposable income over the last several years has gone to paying off that debt. Much more important to the subject, however, is the No. 2 reason why this expansion doesn’t feel like others: wages have seen pathetic growth since the recovery began in its first full year in 2010.

The U.S. Conference of Mayors, The Council on Metro Economies and the website New American City reported in the summer of 2014 that the new jobs created since the recession ended paid on average 23 percent less than the jobs they replaced. The two groups used data from IHS Global Insight that showed the average annual wage in the sectors that lost jobs in the recession — primarily manufacturing and construction — was $61,637. The average annual wage of the new jobs that have been gained — mostly in lodging, retail, health care and social assistance — was $47,171. According to IHS, the 23 percent wage gap following the Great Recession is nearly double that of the recession of 2001-2002, when there was a 12 percent loss in annual earnings during the first few years of recovery.

I won’t address the issue of income inequality much here. It is certainly one of the most divisive political issues out there today. An NBC News and Wall Street Journal poll conducted a year ago showed that 67 percent of Democrats believed that income inequality was an “absolute priority” issue for the federal government to address. In the same poll, just 19 percent of Republicans believed income inequality was an “absolute priority.” Regardless, it’s safe to say that many members of both parties believe that income inequality is a legitimate issue, and that it’s not a good thing when the rich get richer and the poor get poorer in the largest economy in the world. That trend, which has gone on for three decades now, could eventually break the nation’s economy. Or worse, spark a revolution.

Income inequality is a very complex phenomenon. . .why does it occur and what are the factors that make it so difficult to address? Regardless, there is certainly political fallout from the income inequality issue. In a presidential election year, the candidates need to heed these public opinion numbers: 60 percent of the people in this country support raising the minimum wage, 75 percent are in favor of spending more on infrastructure projects and 80 percent believe college should be made more affordable.

Income inequality aside, I think everyone would support higher wages for all if, of course, it didn’t come at the expense of someone else’s pocketbook. Obviously, that is not possible. So, rather than gripe about income inequality and stagnating wages, let’s review some of the policies and ideas out there that could help deal with the issue.

RICHES

Some believe that basic economic principles set wages. I believe the same. However, after years of scanty gains in wages despite robust hiring and falling unemployment, that belief has been tested. Happily, real gains in earnings are finally materializing. The half-percentage-point gain in average hourly earnings in January was the highest in years. And the last six months of gains in real wages was the best six-month period since the recovery began in 2010.

The tightening of the labor market may have finally forced companies to pay more to keep good employees. One measure that the Federal Reserve looks at closely when setting policy supports this. The January 2016 Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) conducted monthly by the Bureau of Labor Statistics showed that the total number of quits in the workforce was 3.1 million. That’s the highest level in a decade. The quits rate of 2.1 percent in the January report was the highest since April 2008. When more people quit their jobs, it means that Americans are earning better paying jobs. It also indicates that workers are confident in the labor market.

Supporting the JOLTS report was a report in February from the job site Indeed. It suggested that over half of U.S. workers will consider applying for a new job this year. The report stated that of 1,052 U.S. workers surveyed, 25 percent said they will definitely seek a new, higher-paying job in 2016. Another 27 percent, the surveyed indicated, said a job hunt is possible this year. The survey also showed that 79 percent of those polled expected to see increased wages this year.

Supporting the JOLTS report was a report in February from the job site Indeed. It suggested that over half of U.S. workers will consider applying for a new job this year. The report stated that of 1,052 U.S. workers surveyed, 25 percent said they will definitely seek a new, higher-paying job in 2016. Another 27 percent, the surveyed indicated, said a job hunt is possible this year. The survey also showed that 79 percent of those polled expected to see increased wages this year.

Walmart made news last year when it raised the minimum wage of its employees by a dollar an hour. A second raise occurred in the winter quarter. Many believe Walmart had to raise its wages up to a minimum of $10 an hour to retain employees. Employee turnover is costly, and the best way to retain employees is to raise wages.

In a story published by Forbes in 2012 titled, “The Story of Henry Ford’s $5 a Day Wages: It’s Not What You Think,” author Tim Worstall made an important point. Worstall maintained that 100 years ago, Henry Ford’s decision to pay his workers more than double what they were previously paid was not because of the widely held belief that he wanted them to be able to afford to buy the cars they were assembling. The author made the claim that Ford’s drastically higher pay had “. . .nothing at all to do with creating a workforce that could afford to buy the products. It was to cut the turnover and training time of the labor force: for yes, in certain circumstances, raising wages can reduce total labor costs,” Worstall wrote.

The noted economist Paul Krugman was quoted in the same article. Krugman said, “Surely the benefits of low turnover and high morale in your workforce come not from paying a high wage, but from paying a high wage ‘compared with other companies’ — and that is precisely what mandating an increase in the minimum wage for all companies cannot accomplish.”

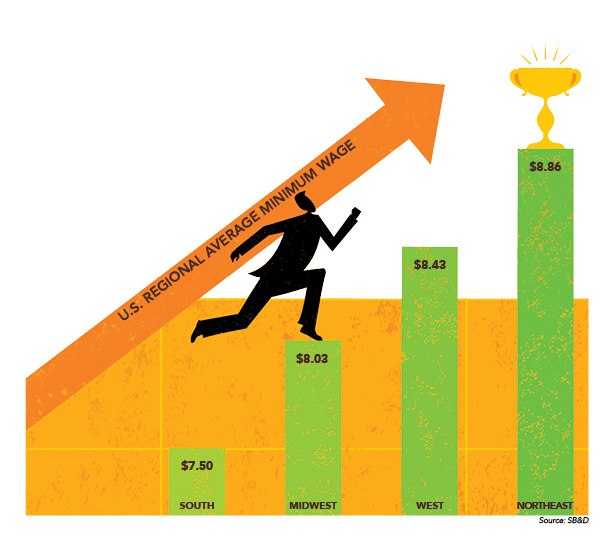

Ah, the minimum wage argument is another political hot potato. . .much like income inequality. Southern states’ average minimum wage is $7.50 — far and away lower than any other U.S. region. Only the minimum wages of Arkansas, Florida, Missouri and West Virginia are higher than the federal minimum wage of $7.25. It should be noted that two of the South’s smallest states — Arkansas and West Virginia — increased their minimum wages to $8.00 and $8.75 respectively this year. Dynamic economies in states such as Georgia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia all have minimum wages of $7.25 an hour.

Except for those who are politically far-right of the Tea Party, no one would argue that anyone in this country can live on $7.25 an hour, much less support a family on that wage. But even the far-right must acknowledge the fact that the bottom 20 percent of wage earners in this country receives almost $50 billion in government assistance each year from the six primary means-tested income support programs. That’s tax-payer money, bro.

Several of the Republicans who were in the presidential race wanted to keep the minimum wage at $7.25 an hour. Bernie Sanders wants to more than double the minimum wage to $15 an hour. That would be a windfall for low-wage workers in the South, since it costs so much less to live here compared to other U.S. regions. Fact is, a $15 minimum wage in many parts of the South simply wouldn’t work. It would be, unquestionably, a job killer. But a $15 floor might work in New York, Chicago and Los Angeles.

It doesn’t make sense to me to have a universal hike in the minimum wage for all states. For example, the minimum wage in New York is $9 an hour. But that $9 only has the purchasing power in New York of $7.36 cents. Here in Birmingham, Ala., the minimum wage is $7.25, but it has the purchasing power of $8.06.

MIT’s Living Wage Calculator exemplifies the differences in earning thresholds and cost of living indexes from around the country. The Living Wage Calculator provides “cost-adjusted estimates of what workers and their families need to make in order to support a basic living in the communities in which they reside.” The developer of the MIT Living Wage Calculator, Dr. Amy Glasmeier, defines a living wage as “the wage needed to cover basic family expenses plus all relevant taxes.”

By using the Living Wage Calculator, you can determine what you need to make for a living wage in every county in the country. In San Francisco County, Calif., it’s $14.37 an hour to achieve a basic living for one adult. The minimum wage in California is $10. In New York County, the living wage according to the MIT Living Wage Calculator is $14.30, but the minimum wage there is $9.00. In contrast, in Birmingham, Ala., (Jefferson County) the minimum wage is $7.25, but the living wage is $10.36 for one adult. Notice the pattern? There is no county in America where a minimum wage earner can support a family, and in almost all counties, the minimum wage can’t even support one adult, according to MIT’s Living Wage Calculator.

Third Way, described by The Wall Street Journal as a “center-left think tank” and by The New York Times as “radical centrists” and “incorrigible pragmatists,” has taken MIT’s Living Wage Calculator further. Third Way proposes establishing five different minimum wage hikes based on the cost of living in metros. Third Way calls their plan “a regional minimum wage.”

Third Way policy adviser Joon Suh writes on the think tank’s website and in the story titled, “Doing the Right Thing, the Right Way: A Regional Minimum Wage,” what he believes is a fair way to go about raising the minimum wage. “Some presidential hopefuls for 2016 have called for a $15 per hour minimum wage to match the wage floors of the highest-cost cities in the nation, but, as we discuss below, a single federal minimum wage makes less and less sense due to the wide cost disparities between cities and states across the country,” Suh wrote.

Third Way proposes to replace the single federal minimum wage with a regional minimum wage with readjustments every three years. The think tank believes that the new wage would range from $9.30 per hour in low cost regions to $11.90 per hour in the high cost areas. That would set the median federal minimum wage at $10.60 per hour, about where the political centrists believe it should be.

It’s my view that five regional federal minimum wage floors are not enough. Some small manufacturers in rural areas of the South would get hammered by a $2-an-hour hike in the minimum wage, particularly in areas like the Mississippi River Delta and Appalachia. Also, I suggest a caveat for young workers just starting out; they would earn possibly a dollar less than a new federal minimum wage of say $10.60 per hour in the first year of employment.

PITCHFORKS

Not all right-leaning capitalists are against raising the federal minimum wage. Entrepreneur Nick Hanauer, a self-proclaimed plutocrat and founder or financier of over 30 companies, sees a future of angry mobs with pitchforks in this country if something isn’t done about income inequality. Hanauer explains in one of his TED Talks, “While people like us plutocrats are living beyond the dreams of avarice, the other 99 percent of our fellow citizens are falling farther behind.”

Hanauer continued by saying, “You see, the problem isn’t that we have some inequality. Some inequality is necessary for a high-functioning capitalist democracy. The problem is that inequality is at historic highs today and it’s getting worse every day. And if wealth, power and income continue to concentrate at the very tippy top, our society will change from a capitalist democracy to a neo-feudalist rentier society like 18th century France. That was France before the revolution and the mobs with the pitchforks.”

Hanauer claims there is no evidence to support the theory that if low wage workers earn a little more, unemployment will escalate and the economy will collapse. In his TED Talk, he also claims that Seattle (his hometown), which voted to raise the minimum wage to $15 per hour by 2017 for some companies, has not seen negative effects from having one of the highest minimum wages in the country. “If trickle-down thinkers were right, then Washington State should have massive unemployment. Seattle should be sliding into the ocean. And yet, Seattle is the fastest-growing big city in the country,” Hanauer maintains.

Hanauer was slightly wrong about the evidence part. Shortly after the minimum wage was raised in Seattle, there were over 1,000 restaurant jobs lost in the city, even though restaurant jobs outside the city limits increased. Additionally, some restaurants in Seattle raised menu prices as much as 21 percent because of the wage hike, and some others reduced worker benefits, such as cutting paid vacation time to just one week a year. But other than that, he’s right; Seattle has not slid into the ocean.

Here is more evidence that the City of Seattle’s wage hike hasn’t yet changed its economy in a negative way. Seattle’s unemployment rate in January 2016 was 4.2 percent. But when the minimum wage was announced in June of 2014 by the Seattle city council, it was 4.4 percent. Ten months later, Seattle’s unemployment rate bottomed out at 3 percent in April 2015, well after the minimum wage hike.

Hanauer may be right about the pitchforks. He asserts that since 1980, wages of CEOs in the U.S. have gone from about 30 times the U.S. median wage to 500 times. I have refrained from writing about income inequality. But that statistic, if true, is a pitchfork organizer.

In Hanauer’s TED Talk, he was even more convincing with this: “So I have a message for my fellow plutocrats and zillionaires and for anyone who lives in a gated bubble world: Wake up. Wake up. It cannot last. Because if we do not do something to fix the glaring economic inequities in our society, the pitchforks will come for us, for no free and open society can long sustain this kind of rising economic inequality. It has never happened. There are no examples. You show me a highly unequal society, and I will show you a police state or an uprising. The pitchforks will come for us if we do not address this. It’s not a matter of if, it’s when. And it will be terrible when they come for everyone, but particularly for people like us plutocrats.”

In Hanauer’s defense, he is a man who has made a payroll with numerous companies, almost all of which he has sold. He was the first non-family member to invest in Amazon.com. One of his companies was purchased by Microsoft and another by Boeing. Many of the arguments for or against income inequality or raising the federal minimum wage come from folks — such as politicians — who have never made a payroll. I have made a payroll with my small company every other week since I was 27 years old. And being the sole owner of a company for 33 years and making a payroll for that long, gives me the right to discuss the issue of the minimum wage. From the research I did for this story, the tiered minimum wage hike proposed by Third Way is the best idea I have seen.

So is raising the minimum wage a job killer or a way for low-wage workers to bolster the economy by increasing their purchasing power? As I wrote in my Southbound column in this issue, raising the federal minimum wage $1 to $8.25 per hour this year, then hiking it again by $1 in 2017, may increase GDP by $400 billion a year according to Seeking Alpha.

Again, because living expenses and business operating costs are vastly different throughout the country, a flat minimum wage floor for all makes no sense at all. And for those wishing to see the wage floor at $15 an hour for all, that’s just not workable. A minimum wage of $15 per hour would certainly be a job killer, particularly in the rural South where unemployment remains high in many areas.

Yet, a “Goldilocks” federal minimum wage hike — not too hot, not too cold — say to $8.25 in many parts of the South and say upwards to $10.25 in California and New York for example, might work for both the Reds and the Blues.

Whether Henry Ford wanted to double his worker’s pay so they could buy the cars they built, or whether it was done to retain human capital, is still up for debate. What is not up for debate is this: hundreds of millions of Americans brandishing torches and pitchforks is not where this nation is headed if the federal government can work together and come up with something that works for all.