It was just 14 years ago that the U.S. economy plunged into the Great Recession, the second-worst recorded economic downturn in the nation’s history. Only the Great Depression was statistically worse, and there are only a handful of Americans left who lived through the deep economic crater that was the 1930s.

Now, remnants of the Great Recession’s damage to the economy, such as slow-motion wage growth, remain. Wages have been rising of late, but not as fast as inflation.

In 2010 and 2011, things started to improve, but there is no question the U.S. economy has never quite recovered from the Great Recession. It’s getting there, though.

Sure, debt incurred by small companies (those that did not close) to keep them afloat 10 years ago has probably been paid off, or just now being paid off. But in many cases, those small companies are now starting from scratch after years of debt that greatly reduced their ability to expand.

In other words, those companies survived by borrowing as much as 40 percent of their gross revenues only to exhale at the finish line, “Yay, the yoke is gone. Let’s make some money.”

These survivors are helping the economy greatly right now. The completion of debt payments by business owners in the depths of the Great Recession is, in many cases, just now showing up in job gains and investment growth.

As a company owner in the Great Recession, you could quit or borrow. There was no in-between for most.

And that recovery is still going on. Unfortunately, a mighty hindrance to recovery is demographics, not economics. We have plenty of consumers paying for services, but because of labor shortages, we cannot fully serve those consumers.

One of my favorite places to eat in the South is Waffle House. You know, the place that serves “smothered” hash browns and other heart-healthy breakfast items? You may have heard that Waffle House never closes — no matter what — it is open around the clock every day of the year. If a Waffle House is closed, there must have been Armageddon — nuclear blast, massive impact from an asteroid, locusts, earthquake or maybe a pandemic. This October, I walked into my closest Waffle House and they said I could not be served. They did not have the staff to serve me. Wait, what, aren’t there just two or three people working at Waffle House on any given day? Okay, back to my thoughts.

One of my favorite places to eat in the South is Waffle House. You know, the place that serves “smothered” hash browns and other heart-healthy breakfast items? You may have heard that Waffle House never closes — no matter what — it is open around the clock every day of the year. If a Waffle House is closed, there must have been Armageddon — nuclear blast, massive impact from an asteroid, locusts, earthquake or maybe a pandemic. This October, I walked into my closest Waffle House and they said I could not be served. They did not have the staff to serve me. Wait, what, aren’t there just two or three people working at Waffle House on any given day? Okay, back to my thoughts.

Other than pesky inflation, the economy is doing pretty well

While services are off the charts, manufacturing dramatically improved in October with automotive again leading the way as the electric vehicle market is now taking that sector to heights it has never seen. Apparently from here on out — or at least in our lifetime — the world is about to become addicted to lithium as we drive from here to there. Beats the two before it — coal and gasoline — I guess.

Just in the fall quarter, the South saw multiple projects the size of actual automotive assembly plants (i.e., $2 billion, 5,000 jobs on average). . .the big kahuna of economic development deals in the South over the last 40 years. For example, Ford announced this fall nearly $12 billion in electric vehicle projects in Tennessee and Kentucky, and Toyota announced a $1.4 billion electric battery project in North Carolina, just to name three big automotive deals. There were others.

The U.S. is truly competitive with other nations worldwide and has been since the end of the Great Recession. That ability to compete is a product of the recovery from the Great Recession and the negative issues COVID-19 placed on the modern-day supply chain of make-it-halfway-around-the-world for one reason: it’s cheaper. The pandemic has proven to us that far-flung supply chains might not be the best idea.

Today, a company can make its products in the largest economy in the world and stay close to its supply chain as cheaply as any developed nation in the world. The days of China dominating U.S. manufacturers are limited. The days of China’s quest to become the largest economy in the world are also limited. Recent data suggests that China will not surpass the United States’ GDP (No. 2 on the world scale) in our lifetime. The reason? China’s cost of living, working and owning a business are going up, up and up! With inflation, so are costs to live, work and own a business in the U.S., but not at the rate of China’s.

It’s not politics, it’s demographics

Both nations — America and China — are hampered, however, when it comes to demographics. The U.S. population is not growing, making the recovery so much more difficult. In other words, as a nation, we are getting very old and there are only a few things we can do about it. There’s (1) increase legal immigration, with of course, regulations and restrictions; (2) accept slower growth; (3) implement tax credits or simply pay couples to have children and/or (4) increase refugee placement in the U.S. with even greater restrictions than immigration.

Today, more people have been forcibly displaced from their homes than at any time since World War ll. Factor in the effects of climate change, and that is not going to change. In fact, it will only get worse (again, it’s not politics, it’s demographics. . .or weather.)

There are now more than 82 million refugees and displaced people around the world. But in a political environment like this one post Trump, there is very little chance of increased immigration or refugee placement in the U.S., even though the numbers (falling tax and Social Security revenues and deposits) clearly show that this country needs one thing to lift its economy—millions more people who work and pay taxes.

But it seems that current political leaders are not interested in, or don’t understand, the data that shows this nation is financially restrained if not financially distressed unless there are more people added to the tax rolls.

If we are supporting so many that are aging out — with federal and state liabilities — and bringing in so few young ones — with new money to the state and feds — how, as a nation, are we going to function? Where is the money going to come from? You can’t sell from an empty wagon, right? In short, it is not coming from retirees or new entries into the labor force because both are straining the bank account.

Where will these much-needed workers come from? Right now, there are only two available sources; immigrants and refugees.

Every year as Baby Boomers age out of the workforce, we get older. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Census Bureau, about 10,000 people on average retired each day in the U.S. in 2020. At the same time, only about 2,200 people turned working age (16) per day. That is not a sustainable pattern. A nation cannot lose 8,000 workers per day (nearly 3 million a year) from its most precious asset — its workforce — and expect a normal and sustained economy.

The ramifications run deep when a nation ages and workers cannot be replaced. We are just now seeing the tip of that spear that will for years perforate our economy. We are bleeding workers. We are bleeding tax payers (at 8,000 people a day) and all those lost taxpayers are now on the United States government’s dime. Sure, we can print more money as we did during the height of the pandemic, but that is also not sustainable. It’s simply math.

What about wages?

Why have wages grown so slowly? It is my belief that whenever there is a downturn as deep as that of 2007 to 2009, employers have a natural excuse for not paying more to employees, “Look around you. Do you see how many companies are closing, going belly-up? We cannot afford to pay you a higher wage. Take the job for what it pays or move on. The company is not profitable. Be thankful you have a job and are on the payroll.” But, as labor becomes less available, that argument can only go so far.

As for the employee or the applicant, how do you combat that even at near or full employment? It defies logic. Full employment equals rising wages, right? That has not been the case for decades. That argument is filled with holes today. While wages have seen an uptick since the pandemic closed everything in the spring of 2020, we are still miles away from getting out of the slow-motion wage crisis. Then again, things are looking up! (More on this later.)

When wages really grew in this country

From the end of World War II through the late 1970s, the United States economy generated rapid wage gains that were widely shared according to many sources, including the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The middle class enjoyed its best years regarding wage growth from the end of World War II to 1979. Wage growth during that time was robust for all sectors.

Yet, for more than 40 years now, the average wage growth has decelerated sharply, with the biggest declines for the bottom and the middle classes. The same pattern of slow and unequal growth continues in the ongoing recovery from the Great Recession from 2010 to today.

Yet, for more than 40 years now, the average wage growth has decelerated sharply, with the biggest declines for the bottom and the middle classes. The same pattern of slow and unequal growth continues in the ongoing recovery from the Great Recession from 2010 to today.

In other words, the practice of trickle-down economics from the Reagan to Trump years was simply a completely failed concept. The rich did not make their money by spending it. They made their money by saving and investing it. You can make that statement political if you want, but just read on.

From the end of the Great Recession to the start of the pandemic, average yearly wages for the bottom 90 percent of workers rose 8.7 percent after adjusting for inflation according to the Economic Policy Institute (EPI). However, pay for most of the top 10 percent rose by 13.2 percent during that time period, while earnings for the top 1 percent jumped 20.4 percent. So, even today, the rich and upper middle class get richer while wages for those at the bottom and in the middle class grow so much slower.

If you start with 1979 numbers — the last year wages for the bottom and middle class rose with gusto — the gap between the highest-paid workers and other Americans is even starker. From 1979 to 2019, average pay increased 26 percent for the bottom 90 percent, 64.1 percent for most of the top 10 percent, an incredible160.3 percent for the top 1 percent, and even more incredible gains on average of 345.2 percent for the top 0.1 percent, according to EPI. Those figures represent some serious gaps in earnings over the last 40-plus years amongst the rich and poor alike, when from 1945 to 1979 the wage gains were even across the board.

So, where are we with wage growth and how sustainable is this shortage of labor?

As employers scramble for workers, wages are finally rising. What looked like a nice increase in workers’ wages in October at 0.4 percent was essentially a mirage. The Department of Labor also reported that while average hourly earnings increased 0.4 percent in October, top-line inflation for the month increased 0.9 percent. So, accounting for inflation, real average hourly earnings actually decreased 0.5 percent for the month.

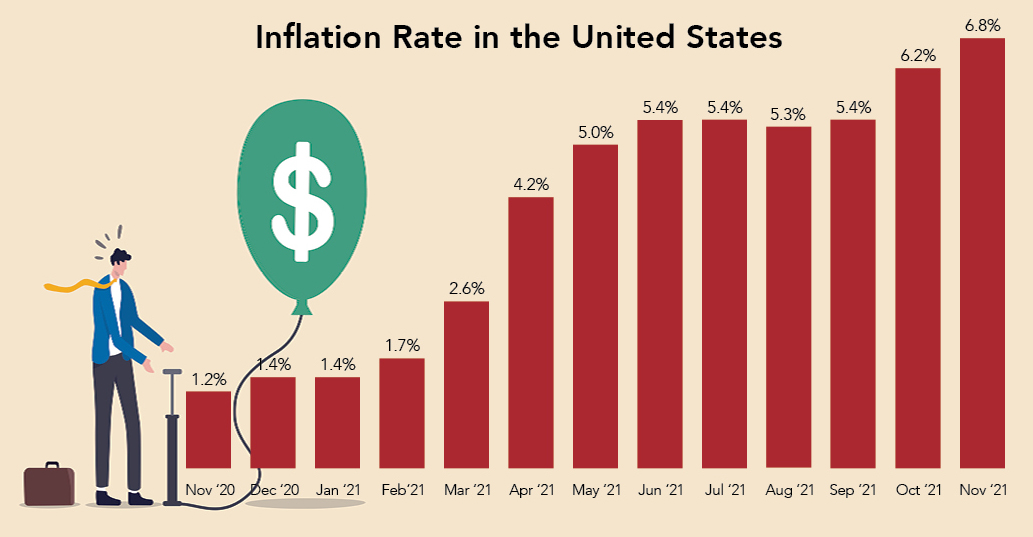

In November, inflation accelerated at its fastest pace since 1982, according to the Labor Department. The consumer price index, which measures the cost of a wide-ranging basket of goods and services, rose 0.8 percent for the month. That is a 6.8 percent increase in the last year.

Wages, riches and pitchforks

In 2016, our cover story was titled “Wages, Riches and Pitchforks.” The story got a lot of attention by the media. In fact, Amazon (without my consent) still sells the piece I wrote as a cheap PDF. (You can read it for free. Just go to https://sb-d.com/magazine/article/wages-riches-pitchforks.)

Here is an excerpt from that article: Not all right-leaning capitalists are against raising the federal minimum wage. Entrepreneur Nick Hanauer, a self-proclaimed plutocrat and founder or financier of over 30 companies, sees a future of angry mobs with pitchforks in this country if something isn’t done about income inequality. Hanauer explains in one of his TED Talks, “While people like us plutocrats are living beyond the dreams of avarice, the other 99 percent of our fellow citizens are falling farther behind.”

Hanauer continued by saying, “You see, the problem isn’t that we have some inequality. Some inequality is necessary for a high-functioning capitalist democracy. The problem is that inequality is at historic highs today and it’s getting worse every day. And if wealth, power and income continue to concentrate at the very tippy top, our society will change from a capitalist democracy to a neo-feudalist rentier society like 18th century France. That was France before the revolution and the mobs with the pitchforks.”

Hanauer claims there is no evidence to support the theory that if low wage workers earn a little more, unemployment will escalate and the economy will collapse. In his TED Talk, he also claims that Seattle (his hometown), which voted to raise the minimum wage to $15 per hour in 2017 for some companies, has not seen negative effects from having one of the highest minimum wages in the country. “If trickle-down thinkers were right, then Washington State should have massive unemployment. Seattle should be sliding into the ocean. And yet, Seattle is the fastest-growing big city in the country,” Hanauer maintains.

“So I have a message for my fellow plutocrats and zillionaires and for anyone who lives in a gated bubble world: Wake up. Wake up. It cannot last. Because if we do not do something to fix the glaring economic inequities in our society, the pitchforks will come for us, for no free and open society can long sustain this kind of rising economic inequality. It has never happened. There are no examples. You show me a highly unequal society, and I will show you a police state or an uprising. The pitchforks will come for us if we do not address this. It’s not a matter of if, it’s when. And it will be terrible when they come for everyone, but particularly for people like us plutocrats.”

Given the economic challenges, why haven’t unions secured a better foothold in the South?

Given the economic challenges, why haven’t unions secured a better foothold in the South?

So, for four decades wage growth has been anemic, we have a stagnant population — an indication that those in their 20s and 30s do not believe they can afford children—and income inequality where the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. That being the case, why does organized labor continue to struggle in the 15 Southern states?

Organized union membership is roughly half that in the South compared to the rest of the country, which is around 5 percent of the labor force. There are some states in the South with union rates of 10 percent or more, but that’s rare.

Twenty-seven states adhere to right-to-work laws; however, every state Southern Business & Development covers is a right-to-work state other than Missouri. A right-to-work law gives workers the freedom to choose whether or not to join a labor union in the workplace. This law also makes it optional for employees in unionized workplaces to pay for union dues or other membership fees required for union representation, whether they are in the union or not.

The law is highly political, with Republicans mostly backing right-to-work legislation in support of big business, and Democrats backing union membership in support of labor and the power of collective bargaining.

While this is not an opinion on right-to-work, there is no question that the South’s efforts to become the engine of the largest economy in the world dilute the influence of labor unions in the region. As entrepreneur Nick Hanauer said earlier in this story, the decline in union membership in the 1960s and 1970s coincided with the decreasing shares of income amongst the 90 percent and increasing income in the top 10 percent. Again, you can make that political all you want, but the numbers indicate that as unions lost their clout, the rich got richer and the poor lost any leverage they had.

Now, that does not mean right-to-work is bad for all. The South’s GDP now makes it the third largest economy in the world, behind only the U.S. and China. As you know, the South was dirt poor 100 years ago. Without right-to-work laws, there is no way the South could have become the fastest growing U.S. region in the largest economy in the world.

Much of that increase in GDP can be attributed to foreign direct investment. Where does Toyota operate most of its assembly plants and its headquarters in North America? Where does Mercedes-Benz have its only U.S. plant and North American headquarters? Where does BMW have its largest North American plant? By the way, none of those facilities are unionized. The answer is all of those facilities operate in the American South.

But that does not mean unions will not try to organize even foreign plants in the South. They have tried with high-profile union drives at Nissan in Mississippi, Boeing in South Carolina and Volkswagen in Tennessee, just to name a few.

Workers, especially at large foreign manufacturing facilities, are extremely lucky to have a job at one of those plants. These facilities already pay way more in wages than the average wage in the South.

Regardless, there is about to be a reckoning when it comes to the South and union activity. In the fall 2021 quarter, Ford, a union company since 1941, announced it is investing $11.4 billion to further its electric vehicle production at a site in Stanton, Tenn., (near Memphis) and Glendale, Ky. Ford will invest $5.6 billion to build batteries and assemble the company’s electric F-Series vehicles. The Kentucky site is a $5.8 billion investment and will include twin battery factories. The two sites will house about 11,000 new jobs.

It will be interesting to see what will happen at those Ford plants when they are up and running. If they unionize, it could change everything in the region. If they don’t, then Ford made an awesome bet.